Hi!

A question came in from a reader - I’ve talked before about how to not do things, and in my recent talk I said “do whatever researchers ask for” isn’t a reasonable strategy. We have finite resources, and we owe it to our communities and to science to focus those resources on the highest-impact things we can be doing. But what does that actually look like when you’ve been asked to do something well out of scope? Below’s a lightly edited version of what I sent back:

It’s important to pay attention to user needs, and thank them for their requests - if nothing else it’s useful data! But we can’t fall into the trap of trying to do everything a researcher asks for (or even every thing many researchers are asking for!). People want a lot of things, and our time and resources are finite. It’s perfectly ok for people to ask us for things, and it’s perfectly ok for us to say no.

Here’s a partial list of examples where it wouldn’t make sense for a team to provide a service that’s asked for:

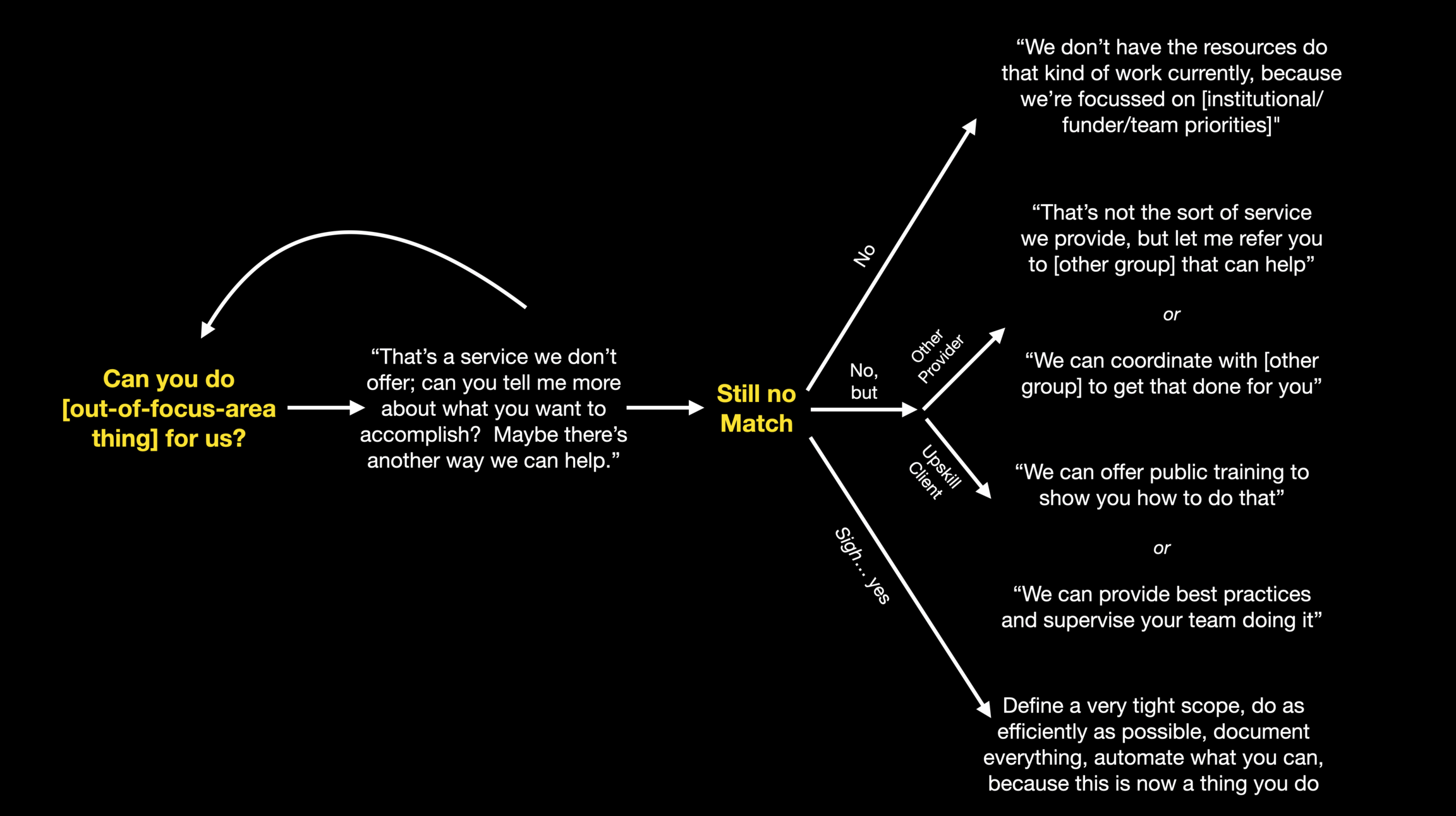

Ok, great. There’s reasons for not doing the thing. But what now? Here’s a few ways to decline providing a service:

Not doing the thing ourselves doesn’t mean we can to support the request; there’s some things we can do without getting fully drawn into the team doing it themselves. A partial list includes:

And we can at least to try to constrain the involvement if it’s something that’ll be ongoing:

But beware of this last option. There’s no such thing as a one-off in a service organization. If you do the thing, one way or another it’s going to be known that this is a thing you do now.

I’ve tried to summarize that as a diagram:

What do you think - do you have other suggestions for our readers? Let me know!

And if you have a question or topic you’d like to see discussed, just email me at any time. Send to jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org, or hit reply to one of these emails. I’ll also set up a simple poll at pollly where people can submit questions pseudonymously and we can vote for priorities - I’ll seed that poll over the weekend with some questions that have come up over time that I’ve never written down answers to.

In the meantime, here’s the roundup! I’ve been involved in a hackathon last week (and the next week), so maybe unconsciously this week’s links tilted a little software-heavy.

We’re hiring - how do we assess candidates for RSE jobs? - Sheffield RSE Team

We’ve talked in the past about providing candidate packets (e.g. Jade Rubick, #84), or about telling candidates what to expect from your interviews (from Julia Evans, way back in #33!). Here’s a great RCD example - the University of Sheffield RSE group giving a clear brief overview of how they assess RSE candidates. Nice!

How to present to executives - Will Larson

A nice complement to last issues’s posts on working with advisory boards, here’s how to present to decision makers like institutional leaders, funders, and advisory board members:

The foundation of communicating effectively with executives is to get a clear understanding of why you’re communicating with them in the first place. […] When you’re communicating with an executive, it’s almost always one of three things: planning, reporting on status, or resolving misalignment.

Although these are distinct activities, your goal is always to extract as much perspective from the executive as possible. Go into the meeting to understand how you can align with their priorities. You’ll come across as strategic and probably leave with enough information to adapt your existing plan to work within the executive’s newly articulated focuses or constraints.

I’d also add that in our case we have another focus area - to advocate for things we need, such as resources or support with particular stakeholders.

Either way, the advice is good - communicating as concisely and effectively as possible is a key part of the process. Larson suggests a SCQA format (I’ve seen variants of this with different letters, but the basic idea is the same):

Beyond that Larson gives several suggestions, all of which are relevant in our context:

A Farewell to XSEDE: A Retrospective & Introduction to the ACCESS Program - Ken Chiacchia, HPCWire

Chiacchia summarises John Town’s presentation (.pptx) describing the history of both incarnations of XSEDE, and referring to the end-of-XSEDE1 and admirably frank end-of-TeraGrid final reports.

The talk gives a great overview of the challenges faced when running inherently multi-institution support for a rapidly diversifying range of needs and users. XSEDE admirably focusses on the users and research for metrics. All research metrics - like the XSEDE choices of papers, citations, and dollars of funding - are inherently limited. But they are vastly closer to tracking outcomes that actually matter than number of jobs run, or cycles or bytes used.

Chiacchia also summarizes talks about the upcoming ACCESS programme which will take over from and evolve XSEDEs models for operations, allocations, and support - I can’t find those talks online, I hope they’ll be public at some point.

Towns also talks about the importance for supporting the increasing professionalization of research systems, software, and data staff. Our newsletter community, helping support the professionalization of the leads and managers of those crucial staff, are an important part of this!

Stop Raising Awareness Already - Ann Christiano & Annie Neimand, Stanford Social Innovation Review

As I’ve said before, our community in research software, systems and data can learn a lot from the nonprofit and social enterprise communities. Those two groups are often lumped together into a category of “mission-driven organizations”. And, after all, that kind of describes our teams, too.

Christiano & Neimand describe the Information Deficit Model, the mental model that begins “If only people knew about…”. I’ve seen teams in our communities fall into the same trap. “If only researchers knew our team was here, ready to help, they’d come knocking on our door.” So they send emails to new faculty, slip in brochures into new grad student arrival materials - and nothing happens. Repeat with “If only researchers knew about the importance of FAIR data” or “about how useful version control is” or “about reproducible workflows” or…

Because it doesn’t work that way, right? We’re probably dimly aware of our own institution’s print shop or machine shop or stats help desk or… and merely knowing that they exist doesn’t change our behaviours. We each could easily list a half-dozen behaviour changes that would improve our lives, and hey that reminds me, how are your 2022 New Year’s resolutions going? Yeah, mine too.

The article talks about awareness leading to harm or backlash. Our cases are less dramatic, but there’s certainly anecdotes of, e.g., “reproducible open science/good software development practices/cluster computing is the right way to do things” actually turning people away from teams that could help them. People don’t want to be seen to be doing the “wrong” thing.

In the context of public interest journalism, Christiano & Neimand describe a four step approach:

For us, we want people to not just know about but engage with our teams, so we’d want to make specific targeted outreach, find out what they want and need, make it clear what we can do and help with for the teams, show how that could lead to more of what they want. That’s almost always going to be the much more labour intensive individual interaction rather than just sending out broadcast messages for “awareness”. But getting people engaged is hard work.

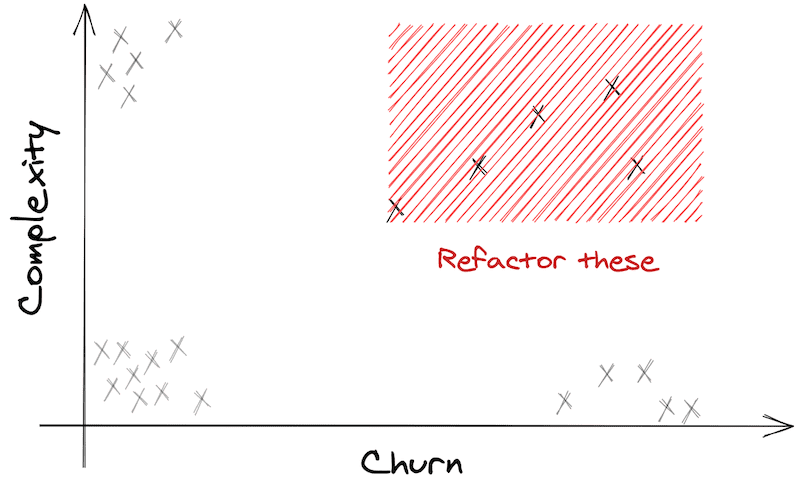

What NOT to fix in a Legacy Codebase - Nicolas Carlo

We work with a lot of legacy code, and the temptation is just to leave it completely alone until we get so sick and tired of it that we just want to rewrite the whole thing. But code bases are large, and generally known-working (or at least the limitations are well-understood). Carlo counsels us to focus on the highest-impact work (which is good advice for managers and leads in general!)

Relatedly, I’ve been meaning to read Marianne Bellotti’s Kill It With Fire. People seem to really like it. It also takes a very pragmatic view of working with existing software, and not getting carried away with massive rewrites of code that isn’t causing problems. Has anyone read it and have some comments?

Debug logs are a code smell - Jonathan Hall

Logs, too, are something that a lot of research software either does not have at all, or that expose every printf("Here! 123\n") debug statement that was ever useful. Neither of those are great.

Hall has an analogy I like here - the ssh debug statements in verbose mode:

The important thing to recognize here is that (usually) this type of debugging output does not exist to debug the program itself (

sshin this example), but it exists to help debug a larger process (i.e. network communication). As such, it needs to be well written, (grammar/spell check advised), clear, and descriptive, because it’s part of the program’s UI.

Logs are to describe (in increasing detail) what a program did, and maybe why it did it. That’s often useful in knowing what part of a code base to take a look at! But active debugging statements are a debugging tool one might use in the moment, not useful logging behaviour.

Write The Docs has a really good “beginners guide to writing documentation” page focussed on the why and hows, based on an earlier presentation.

If you really love your project, document it, and let other people use it.

Solving Society’s Big Problems Means Funding More Than Supercomputers - Tobias Mann, The Next Platform

Playing catch-up in building an open research commons - Bourne et al, Science

I am heartened to see, now that people can run HPL at a new round number of flops per second, that the community’s attention is starting to turn back to more important research computing and data needs. Mann summarizes and gives some context to Bourne et al.’s article calling for more data (and associated compute, and of course software) resources along the lines of open research commons. Some regions are doing passably well at this (like Europe, although sustainability remains a challenge) as well as some fields, but elsewhere it’s pretty grim.

We Learn Systems by Changing Them - Jessica Kerr

I don’t think Kerr’s premise is controversial in our community - new sysadmins and ops staff learn by building small systems or components of systems, for instance. And whenever even experienced staff make changes to long running systems, there are almost always Exciting New Discoveries.

And yet the tendency is to keep research computing systems as encased in amber as possible, frozen in stasis so that things don’t break. That’s a reasonable goal, but it also leads to loss of learning about what’s going on. It leads to fading understanding about the current state of the system and its interactions as previous mental models grow out of date.

This is the basic idea behind “chaos monkey” or disasterpiece theatre (#5) approaches, where changes are deliberately introduced to systems to test understanding of the system. Of course, for that to work, there has to be a clear plan, hypotheses tested, and new knowledge documented. Or, as myth busters reminds us:

There seems like a surprising level of interest in the C++ community for Carbon, a Google-initiated project. Carbon explicitly aims to be a path towards a successor to C++, maintaining source code interoperability with existing C++ codebases but breaking ABI compatibility (after a controversial vote in the C++ committee to not do such a thing). It has very Rust-inspired syntax but hews much more closely to a C++ view of the world.

Some cool things are making it into C23, including embed for embedding binary data directly into executables (this will reduce the need for so many hacky convert-to-ASCII scripts and so much makefile chicanery), along with C++-style auto, nullptr, true and false keywords, and constexpr.

A very cool hands-on practical introduction to deep learning by the fast.ai team. (They also have a solid data ethics course).

The case against symbolic links.

Getting good Rust performance - the Rust Performance book.

Pleasant debugging with GDB and DDD. DDD’s data plotting capabilities made it very useful back in the day for working with small numerical codes. Sadly it seems to be moribund now, and there don’t seem to be any alternatives that have anything like DDD’s data visualization capabilities.

This is cool - making use of H5Web (serving HDF5 data) for purely local data visualization within VSCode - vscode-h5web.

Solving ODEs with Haskel and Taylor Series.

A complicated machine with simple interaction (pull the black handle of the rope) written entirely in CSS.

Microsoft’s FOSS fund is now offering (modest) support for curl, as well as GNOME, MSYS2, Leaflet, and systemd. Which, you know, good, and it would be awesome if we could get routine funding for research-critical open source software other than from the goodness of tech giants’ hearts.

Lego is issuing a new 70s-style Space Lego set in August. Pew pew! Zoom!

Finally, lasers have a use for us theorists and computational researchers. Ultrafast cold-brewing of coffee by picosecond-pulsed laser extraction. Which, when you think about it, is also Pew pew! Zoom!

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.