Hi!

We now have 200 members of our community; people who care about research computing and data teams, their potential, and the importance of leading them professionally.

So, welcome new readers! Some resources that might be useful:

Speaking of resources and online communities: thing that we did for a while in the first year of the newsletter was a recurring “AMA (Ask Managers Anything)” section. Readers would send in questions (anonymously, by default), I’d take a whack at answering in an issue and then we’d solicit answers from readers which we’d include in the next issue (also anonymous by default).

I think enough time has passed and we’ve got a critical mass of new readers, so let’s try that again. If you have questions you’d like to hear feedback on, give our community a shout! Hit reply (emails only go to me) or email jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org, and I’ll post your questions in the next issue. And of course if you have anything else you want to share with the community, or suggestions or feedback on the newsletter, please also send them along.

In the last issue, we were talking about the benefits of having worked in or around research in our line of work, and I talked about the basic mindset of research: “So while ‘growth mindset’ and ‘comfort with uncertainty’ seem like empty phrases to us, they are high-achieving traits in other parts of the world.”

A reader chimed in share their experience having seen the same thing:

Yes. It took me many, many years to realise that having a PhD marks me out as highly skilled in the majority of organisations. We think it is normal to be surrounded by high achievers – my own background is from CERN. We do not realise that many organisations have people who do quite mundane work.

There’s other examples of the strengths we bring from spending part of our career in and around research, too. Here’s an article from earlier in the year saying that having multiple areas of tech expertise is a “superpower”. It’s pretty common in our profession to have a research area of expertise and a tech area of expertise, and I think that’s a superpower too, for the same reasons given in that article. It improves communication, strengthens links between groups, helps us understand how the work connects to research, and helps find better solutions.

With that, on to this week’s roundup!

Everyone’s a great manager until they start managing - Jonathan and Melissa Nightingale, Raw Signal Group

Four mistakes I made as a new manager - AbdulFattah Popoolah, LeadDev

What you give up when moving into engineering management - Karl Hughes, Stack Overflow Blog

When we see people do a different job than we do — especially when they do it very well or very poorly — it’s easy to think “that doesn’t look so hard”. Plumbing, graphic design, customer-facing roles; we watch for a while and figure “I could do that”. And you know, we probably could, eventually. Because it is way harder than it looks, for almost any value of “it”. Competence is hard-won. The people performing those roles are avoiding (or ignoring) a lot of potential problems we’re not aware of, with background knowledge we don’t have, deftly performing practiced tasks that we’d botch the first dozen times through.

It almost always takes us much longer than we imagine to claw our way up to a basic level of competence in a new field. In areas where the feedback loop is slow, it can take still longer. Absent prompt signals to the contrary, you can quickly get into Dunning-Kruger territory where you fool yourself into believing you’re doing much better than you are.

And, well, welcome to leadership and management. When I and others say “management isn’t a promotion, it’s a career change”, this is what we mean. It’s a whole ‘nuther job, where your experiences from your previous job help but also hinder you.

The Nightingales have a nice article that’s hard to summarize, but I like their section headers as an overview - “In theory it’s easy.” “In practice it’s hard.” And, crucially, “The management is in the doing”. Good management - assuming you’re in a reasonable situation where success is possible - is a learnable set of skills and behaviours, that have to be done and redone until they’re practiced. And then have to continue being done. You will keep developing mastery of those skills for as long as you keep working at it.

(In our line of work, Management isn’t the only “looks easy; after all, I’ve been on the other side of it and know what not to do” profession we get thrust into. Teaching and training is another set of extremely important activities that people spend their entire life studying and learning. And we get tossed into it with zero education or support.)

Popoolah talks about the big categories of mistakes he made as a new manager (which overlap quite a bit with the “Help, I’m a Manager” talk above. Fundamentally, he didn’t know what the job was, so he had trouble doing it. He didn’t have a clear vision for the team; he had trouble giving constructive feedback; the first departure on his team threw him for a loop; and he kept trying to be a team lead instead of a manager. It’s a good short summary of the problems a lot of new managers face.

Hughes talks more concretely about the things that are given up on the management path: focus time; short feedback cycles; conflict avoidance; making technical decisions; and staying up to date technically. It doesn’t have to be given up forever — I’m back on my third tour of duty as an individual contributor! — but those are just not part of the job of a manager.

Management Development As Skincare Regimen (Twitter Thread) - Angela Riggs

So how should you start learning the new skills you need to be a manager? Riggs has one way to think about it.

I’m always on the lookout for new analogies for management, leadership, and strategy. For management I personally like sports metaphors, but they’re so overused that every ounce of insight that can be extracted from those comparisons have long been exploited. I’ve always found war and combat metaphors distasteful and aggrandizing, and now especially. Our jobs are tough, but no one’s getting killed.

In #42 there was a pretty helpful comparison to TV show writing, which is another example of collaboratively creating something new. Here Riggs uses the metaphor of adopting a skincare routine. It’s not something you do all at once; it’s something you start with an eye towards the problems you’re trying to solve. You add and change products as needed. You test each change to see if it advances your goals, even though it can take some time to see the result. You have to unlearn old things (exfoliation!). And of course you get input from others trying to solve similar problems.

The Thirty Minute Rule - Daniel Roy Greenfield

We’ve talked a lot about having explicit expectations in your team, especially around communications. It’s been on my mind having changed teams very recently.

Your team does have expectations about how people work together. (You’ll find this out very quickly if a new team member starts behaving very differently from team norms!) The only question: do you have those expectations written down somewhere? Having expectations explicit makes it easier for new team members to spin up, and for experienced members to mentor juniors and trainees.

If you don’t have such expectations explicit, one good target to start with is: how long should someone wrestle with something on their own before bringing other team members (or stakeholders) in?

You do have expectations about this. If someone was spinning their wheels for two weeks making no progress because they were stuck on something someone else could have told them, you’d be annoyed. You’d also be annoyed if someone constantly asked on the #general channel on slack the second something came up they didn’t know.

Greenfield suggests a 30 minute rule; don’t let people get stuck because of something they don’t know for longer than 30 minutes. Maybe in your team, with the kind of work you do, it’s an hour, or a workday, or 15 minutes. It almost doesn’t matter. Pick something that feels right, and bring it up with your team at your next team meeting and see if they agree. Make changes as necessary. Then write it down somewhere and put it in your onboarding documents; from there you can build up to other shared team expectations.

Run your day, don’t let the day run you - Kahlil Lechelt

A manager or leads’ day in research computing is much busier and filled with a wider variety of demands than we’re used to as an IC. It’s vital to maintain some sort of control over the tasks you’re working on. Lechelt gives good advice:

The Painfully Shy Developer’s Guide to Networking for a Better Job - Sam Julien

Conferences are starting to happen in person again. A lot of us at the intersection of computing and research are pretty committed introverts. Being in a group of mostly strangers in person, or even online, can be challenging.

But meeting others in your work community and developing professional relationships is important. It’s not just about finding new jobs! It helps us find and share relevant ideas; helps us hone our craft; and helps build our community of practice.

Julien gives time-honoured advice that works for him; maybe it’ll help you, or someone on your team:

Good mentors boost integrity, survey finds - Erik te Roller in Haarlem, Research Professional News

An important part of our jobs is mentoring juniors and trainees in our team, but also from research groups. Indeed, even the PIs we work with we’re often mentoring in some kid of technical area.

It turns out that matters in a number of surprising ways. Juniors who are well-mentored then go on to be less likely to commit research misconduct. It’s not hard to imagine how that might be; they’re less lost, less at-sea, and feel more connection to the research community. If we have a research trainee working with us, and we show them how to get their work done and help them when they need it, they’re going to struggle less, maybe less likely to cut corners in a moment of desperation. It’s really hard to come back once you’ve started cutting corners!

What Does and Doesn’t Happen After You Specialize? - David Baker

Research computing and data has a large consulting component, and for that part of the job we can learn a lot from other consultants. The basic job - understand some aspect of a client’s work, uncover their problems, connect their problem to our specific expertise, and help them construct a solution - is the same in any field.

Consultants in other fields are much more successful when they specialize. As long-term readers will know, I strongly recommend research computing and data teams, especially (but not exclusively) consulting and software development teams, devote themselves to a very small number of sub-specialties, unless institutional imperatives flat-out forbid it.

Again, your team already has things that it’s better at and things that it’s less good at; it’s just a matter of making that specialization explicit. By doing so, you can further develop your teams strengths, stop spinning your wheels (and wasting your stakeholders time) on projects and products that are less likely to succeed, and make it easier for researchers to know that you’re the team they should contact.

Baker helps other consultants specialize, and knows that making the change to narrowing the focus is scary. Here he tries to make it less scary by pointing out that the day after you start your specialization… not a lot changes.

When a seismic network failed, citizen science stepped in - Alka Tripathy-Lang, Ars Technica

Citizen seismology helps decipher the 2021 Haiti earthquake - Calais et al., Science (2022)

Despite all the buzziness of it, I’m really optimistic about smart devices for research - to be able to build networks of sensors to collect data without requiring researchers to build and maintain large amounts of infrastructure.

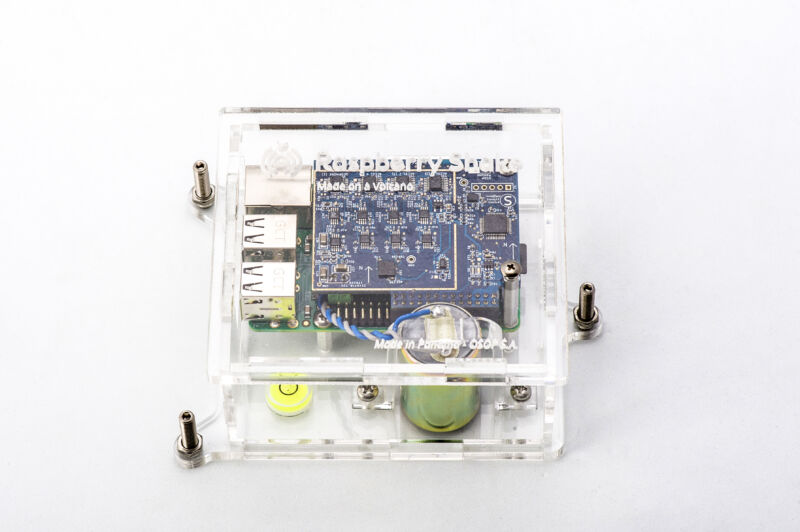

Here’s an example of such a project. Haiti, for a variety of historical reasons (including having to pay reparations to French slaveholders for daring to declare independence) has problems maintaining complex infrastructure. That includes seismograph networks, which is a problem in a seismographical active part of the world. In steps comes Sismo@Ayiti, a citizen-science effort connecting volunteers with small Raspberry Pi devices that can be placed in their house, sending vibration data to a central server (you can see the live data here). Tripathy-Lang gives a great writeup; these devices are noisy (in people’s homes), but the noise is uncorrelated, and there’s many devices, so signal processing and machine learning can uncover good overall signal. In particular, it was enough to disentangle the fairly complex event that was the 2021 earthquake.

How we ship GitHub Mobile every week - Taehun Kim, GitHub Engineering Blog

An interesting behind-the-scenes look at what’s involved in shipping releases regularly.

Ignoring the mobile app parts for a moment, which is something most of us don’t deal with, I was surprised by how vanilla and routine the tools used were. The main work has gone into developing processes and forms to automate what can be automated and add checklists. The tools and processes they use could all be readily adopted by a research software team. The exceptions are trivial - e.g. they keep track of whose turn it is to do which task using an on-call-management tool, because they have it, but one could just as easily use a google sheet.

Their process is:

Essential Open Source Software for Science (Cycle 5) - Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, Letters of Intent due 19 Apr

I’d love to not post the CZI software calls every time they’re out, mixing it up a little bit instead. But no one else is doing the work of routinely funding maintenance of important open-source scientific software, so here we are.

Focus areas are foundational tools and infrastructure, and domain-specific tools for infectious diseases, imaging, and single-cell biology. Applications can request $50-200k/yr for two years. If invited to submit a full application, it’s a tight turnaround - notices go out May 5, applications are due 2 June.

How Google, Twitter, and Spotify built a culture of documentation - Nik Begley

Documentation can too easily fall behind. It’s kind of everyone’s job, so it’s no one’s job; and people are focussed on shipping new code not updated documents.

Begeley summarizes talks from teams at Google, Twitter, and Spotify about how those teams improved their documentation and then kept it better. What I found interesting here is how similar the cases were to each other, but also to a case study on research computing software, the Tasmanian library, that we covered back in #43.

Common features of the approaches were:

It’s fascinating to me that the problems are the same even at huge corporate teams, and that the solutions are so similar and, well, do-able.

I’ve been talking about NVIDIA’s GTC as a worthwhile event back since #15; ignoring it now just because I work there seems a bit much. So check out the session catalog, and register if you see something that interests you. Registration for the sessions are free. Those trainings that do cost money are not very expensive and are pretty uniformly recognized as being quite good.

Breaking Data Silos Open with an Apache Arrow Platform - Daniel Robinson, The Next Platform

This is an interesting example of what I think is a positive development for research computing and data. An open source standard and tool (Apache Arrow here, an efficient in-memory representation of columns of data) will be supported by new company Voltron Data (which just announced a successful seed round) with development and enterprise support and software tiers for those who want it.

Expertise comes from people with experience in data analytics and people with HPC expertise such as well known HPCer Fernanda Foertter, which makes me hopeful that this is something that could be useful across research computing. And enterprise support subsidizing open-source tools - especially one which serves as something of an interoperability layer for data on disk and in memory - is a powerful approach for keeping those tools maintained and usable.

Some very nice detailed articles on working with Postgres - Postgres Auditing in 150 lines of SQL, How we optimized PostgreSQL queries 100x, and using views for zero-downtime schema migration.

Getting started with ML training using Intel’s oneAPI AI Analytics Toolkit.

The Dirty Pipe Vulnerability - Max Kellermann

Linux has been bitten by its most high-severity vulnerability in years - Dan Goodin, Ars Technica

New Linux bug gives root on all major distros, exploit released - Lawrence Abrams, Bleeping Computer

Hopefully this isn’t the first you’re reading of this (why do these things always break on Mondays?). I’ve collected the best write-ups I saw; there’s local escalation exploits published, and it wouldn’t shock me to hear that there’s worse circulating around. Kellerman identified the bug, and his article tells the story of how it was found. It’s a kernel error involving the interactions of pipes and page caches in memory.

The “good” news is that a lot of research computing systems are still on RHEL7 or the moral equivalent, which has kernels earlier than the roughly 5.8 where this started being exploitable. Still, check your versions of everything and update as soon as you can if needed.

It’s amazing anything works at all. Of course we live in an era when business phone systems are being used actively exploited to take part in DDoS attacks, so, you know.

Understanding wait time versus utilization - from reading Phoenix Project - Zhiqiang Qiao

Every so often I see technologists rediscover a very widely known result in operations research - introductory textbook stuff, really. Wait times (or other bad behaviour) start rocketing upwards once we get to high (somewhere between 80% - 90%) utilization. You see this in equipment, and teams, of course, too. Teams, whether they’re cash registers or software developers, start getting into trouble at sustained high “utilization rates”, e.g. overwork.

And yet, a typical metric for the systems we run for researchers includes utilization, with an understanding that higher is better. After all, if we have one system at 75% utilization and another at 90%, haven’t we wasted money on the 75% one by over-building?

Of course, Qiao points out that even if you discard utilization as a metric, wait time isn’t the only metric we might care about either. Getting the most important tasks through the queue, whether that’s software features or compute jobs, is what’s important.

Metrics matter! We bake in all kinds of pathological incentives when we choose KPIs based on what’s easily measured (typically technology or input based) instead of what actually matters (supporting new and high-impact research outputs).

SSH Key Rotation with the POSIX Shell - Sunset Nears for Elderly Keys - Charles Fisher

Keys that never change are dangerous if something happens; Fisher shows that it’s straightforward to write a simple script for rotating your ssh keys. The primitives - ssh-keygen and ssh-copy-id - are most of what you need; this wrapper script handles the details. The only thing that’s tricky (and dangerous!) to do automatically is removing the old key. Fisher walks you through the process to build up the tooling in a way you’re comfortable with.

A quick walkthrough of setting up docker in rootless mode.

Reinventing High Performance Computing: Challenges and Opportunities - Daniel Reed, Dennis Gannon, Jack Dongarra, arXiv

Will HPC be eaten by Hyperscalers and Clouds? - Timothy Prickett Morgan, The Next Platform

Looking for a Singularity Event for Scientific Computing - Jeffrey Burt, The Next Platform

Bad News for Cloud Computing: OpenStack Use Plummets and Discounts Dry Up - Lawrence E Hecht, The New Stack

Reed published a blogpost in early February, which has been focussed, fleshed out, and joined by Gannon and Dongarra into a preprint on arXiv. Morgan summarizes the paper well in his article, starting with this sum-up:

…we get a fascinating historical view of HPC systems and then some straight talk about how the HPC industry needs to collaborate more tightly with the hyperscalers and cloud builders for a lot of technical and economic reasons.

In a time of Moore’s law ending, where the cloud companies and hyperscalers comically dwarf the old-school computer vendors, and when research computing is ever-broadening to a wider and wider range of important problems to solve, the old ways of building systems just aren’t going to work. I won’t try to summarize Morgan’s summary; if this interests you at all, I’d highly recommend starting with Morgan’s article, going to the paper as needed.

But I would like to tie it into two other articles.

First is Burt reporting on BP’s John Etgen’s keynote at the recent EnergyHPC (née Rice Oil & Gas) conference. Etgen laments the lack of an “explosion in innovation” in HPC that is happening in AI, clouds, and even once-staid fields like databases. He points to a lack of increasing specialization in HPC, lack of composable components, and of new software:

That said, if the field was in singularity, “you’d see an exploding diversity of applications. Do you feel like we’re seeing an exploding diversity of applications? In computational fluid dynamics, I think the answer is no. In computational seismology, the answer is definitely no. In reservoir engineering, I think the answer is no. Maybe there’s some other scientific fields that actually have an exploding diversity of applications in scientific computing. Maybe, but it’s kind of iffy. I’m not sure I see that.”

Finally is Hecht’s suprising-to-me report of four years of survey data about on-prem private clouds. The first fact is discouraging but maybe not surprising: OpenStack use is plummeting, dropping by more than half over the past three years. This is really bad news for people hoping that OpenStack will continue to be supported and extended.

More surprising to me is that use of enterprise stalwarts like VMWare (often used for “enterprise” vs “research computing” workloads) is also plummeting. The only options that are clearly growing are AWS Outposts (which will ship a rack or individual servers of managed AWS servers to your machine room) or Azure Stack (which will let you buy your own Azure-certified gear and run the Azure managed stack atop it, charging per core).

I think we need to start getting used to the idea that trillion-dollar cloud providers are better at running computing systems than siloed teams of 5 or 12 or 50 can manage, and much better at writing the tools to support management of the system. If that’s true then even on-prem systems 10 years from now might mostly have commercially-supported control planes from the cloud providers running atop. That’s different, in the sense of fewer choices, than paying for commercial support for a scheduler and Lustre, but is it so different that we can’t accept it? I guess we’ll find out.

Here’s a nice blog post explaining when to use AWS ParallelCluster vs AWS Batch.

The N8 Centre of Excellence in Computationally Intensive Research (N8CIR) is hosting a digital research infrastructure retreat the last week in March in Manchester. It covers strategy, grant writing, new technologies, developing a profession - it honestly looks like a great event. Registration is still open.

So I have a Windows computer for work for the first time since Windows 3.11. For those computers I actually type on (as opposed to those I ssh into) I’ve been using Mac since… 2006? On the new machine I can use Ubuntu via WSL2, a browser is a browser, and VSCode & Teams & Slack are all cross platform, so it’s mostly ok… except for the frickin’ keyboard shortcuts.

Oh yeah, and frickin’ paths. Here’s the history of how Windows came to use the wrong slash. It’s all DEC’s fault, stemming from how options were passed to commands for the TOPS-10.

An open-source microscope built using Lego bricks, 3D-printing, Arduino, and Raspberry pi. By IBM(?).

Sure, word processors are great and everything, but sometimes I prefer to use an older, text-based markup language to write documents that get beautifully typeset. And if you use the same one, too, great news - that too, groff, now has an IDE. Written in Pascal, so you know it’s good. (Heirloom troff seems to be the current best implementation, by the way).

The history of the inverse-T arrow key arrangement.

Javascript might be getting mypy style type hinting. One can only hope that, like mypy, it starts from there and grows outwards.

Make oddly soothing art with vector fields.

Using Google Sheets as a database to back a website using ROAPI and Replit for API hosting.

Literate programming/notebook style documents for the mechanized proofs that come out of theorem provers.

The people creating a small community around tiny computing.

A deep dive into ED25519 signatures.

Small thermal models in the browser.

Here’s a C cross-compiler for the 6809 for those of us who had a TRS-80 Color Computer. To heck with those fancy kids with their Commodores.

Oh, fine. For you Commodore kids, here’s creating a Commodore C-64 cartridge with a Raspberry Pi Pico.

Quantum Computing from a statistical point of view (authors PDF).

A debugging story of a super hard-to-track-down bug involving infiniband, GPUs, forking a new process, and malloc.

Implementing the lambda calculus in 392 bytes.

And that’s it for another week. Let me know what you thought, or if you have anything you’d like to share about the newsletter or management. Just email me or reply to this newsletter if you get it in your inbox.

Have a great weekend, and good luck in the coming week with your research computing team,

Jonathan

Research computing - the intertwined streams of software development, systems, data management and analysis - is much more than technology. It’s teams, it’s communities, it’s product management - it’s people. It’s also one of the most important ways we can be supporting science, scholarship, and R&D today.

So research computing teams are too important to research to be managed poorly. But no one teaches us how to be effective managers and leaders in academia. We have an advantage, though - working in research collaborations have taught us the advanced management skills, but not the basics.

This newsletter focusses on providing new and experienced research computing and data managers the tools they need to be good managers without the stress, and to help their teams achieve great results and grow their careers.