Research computing and data, as a community, has an inferiority complex. And it’s a problem.

This week I saw yet another press release - I won’t link to it, there’s no point in calling out this University or team in particular, it’s not like they’re sole offenders here - about how their new HPC cluster would “transform research”. Look — no it won’t. What would that even mean? Transform it into what? A biscuit? Rugby?

The infuriating thing here is that by all accounts, this was a good and useful procurement. Not only did it increase capacity (even if not to the “capacity knows no bounds” limit specified in the press release) but also the range of capabilities, with heterogenous nodes and a more flexible scheduler. That mean the existing researchers will have access to more resources, and it looks like it’ll be easier to provide support to a wider range of researchers, including those whose needs weren’t being met before.

This is how we support research. It may feel incremental in the day-to-day, but on aggregate, over time, it’s not. We connect researchers to our teams’ wide-ranging expertise. We get them access to compute and data resources. We use our interdisciplinary vantage point to connect dots between fields - not just their domain and computers, but (say) bioinformatics needs and methods being used in astronomy - to make new lines of inquiry feasible. We’re scanning the literature, trying new gear, wrestling with new tools, testing new methods - constantly investing time and effort into understanding new approaches and technologies so that when our researchers need them, we’ll be ready. We - our expertise, our contacts, our teams, our resources - are some of the frickin’ giants that our researchers clamber onto the shoulders of so that they can see further. Not just one or two researchers either, but dozens or hundreds of them at a time. We go to where they are, learn from their surroundings, and work with them to create a plan to help lift them up.

And we don’t feel like it’s enough.

Some of us came from research, and we feel twinges of regret of not being on the front lines ourselves pouring over the results from our satellites or spectrometers or specimens. We were trained to be doing the research, and supporting it feels lesser-than somehow.

Others of us come from the computing side, and we feel the siren call of the tech industry, where we could be making three times the salary working for brand-name companies, playing with the coolest tech and giving conference talks alongside other tech industry giants, doing the latest SRE/DevOps/Kubernetes/Serverless cool stuff. We feel abandoned in the backwater, atrophying and undervalued.

Too many of us feel like what we’re doing isn’t enough, that our efforts aren’t significant. And to try to dress it up, to make it sound better, we let our Uni’s PR office or vendors bully us into putting our name to nonsense strings of syllables like “transforming research”.

Here’s the thing - the researchers we support are also not going to transform research by themselves. Research, despite the stories we tell, are not about individual heroes. Where individuals do play an outsized role it’s about the vision, not the work. The work of research, the work of science is a team effort, a community effort, a constant stream of incremental progress and double checking and investigation and false starts and new leads. In aggregate, over time, frontiers shift and discoveries are made and incredible new things become possible.

If you care about advancing knowledge and know something about both computing and research, the highest-leverage way to spend your time right now, today, is supporting a community of researchers with technology. Not being a researcher, not working on technology, but connecting the two. Being that bridge between fields, between needs and opportunities. The math is simple - as a researcher you can pursue a couple lines of research deeply. In research computing, you can accelerate the work, amplify the abilities, of tens or hundreds of researchers, or of entire research communities. By developing and maintaining software tools or systems or data analysis pipelines or curated data resources your team can make entire fields work a bit better.

I’m not trying to make individuals feel better about their life choices here. That’s not my skillset, and I make a crummy cheerleader. (In grad school, I was given a set of bright coloured pencils with “I have a positive attitude!” stamped on them because my friends agreed that it was a hilarious gift to give me. I do not have a positive attitude.)

What I do want to do, through this newsletter and otherwise, is to make the case that research computing and data is a real profession, an important profession - honestly, one of the most important, most impactful, professions in this moment. Whether our researchers are working on climate change or spread of disinformation or clean energy technologies or health research or something else, they need all of the help — all of our help — they can get.

I’m tired of seeing new research computing team managers and leaders given absolutely no support or training or guidance. I’m tired of the resulting poorly-run research computing teams, seeing team members who aren’t getting the coaching or support they deserve, observing catch-as-catch-can “strategies” for choosing projects and next steps, watching hopeless project plans crumble, sitting through aimless meetings, seeing leaders flailing and stressed because their directors, or academia, or the tech industry, don’t think research computing is important enough or worthy enough to take seriously. I’m tired of seeing that those departments or institutions don’t care to oversee research computing teams with professionalism, or treat it as a capability to develop and nurture and grow and engage and retain.

None of us individually can fix the institutions. What we can do is gather together cohorts of managers, leaders, or those thinking of becoming same, who can make things better in our own domains. Research computing managers and leaders who know the technology, know research, but also care about managing people, shaping projects, setting strategies, and getting things done. Managers and leaders who will grow their own skills and train the next cohort of managers and leaders. Managers and leaders who know that research computing is important, and so worth being done with professionalism, and that research computing teams are important, and so worth being managed with professionalism.

Hopefully, over time, efforts like this newsletter will help.

If you ever feel like you need some help that your organization isn’t giving, some guidance or questions, feel free to hit reply to one of these emails, send me a note at jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org, or set up a quick call with me. As this newsletter community gets closer to having a critical mass, we’ll look into some ways we can start coming together as a group to share experience, knowledge, and advice together.

In the meantime, for the love of God, don’t let your University comms department put absurd words in your mouth just because you worry the actual work your team does isn’t flashy enough.

Anyway, that’s a bit long this time, sorry - on to the roundup!

My Lessons from Interviewing 400+ Engineers Over Three Startups - Marco Rogers, First Round Review

Getting to yes: solving engineering manager hiring loops that reject every candidate - Will Larson

Guides to Interviewing at Notion - Notion

Interviewing at GitLab - GitLab

Here we have a collection of interlocking articles and resources on interviewing for technology jobs.

The parallels between startups and research computing are made explicit as often as they should be. There’s a lot of need for tolerating uncertainty - in both cases, people are defining the problem while working on a solution. And with a small team but many changing things to do, everyone has to be adaptable enough to be able to do a little bit of a lot.

In the first article, Rogers talks about his experience hiring 80 developers and ops staff for three startups - and his concern that many organizations don’t view interviewing and hiring as the crucial activities that they are.

Rogers dismisses interviewing purely for technical knowledge and skills - in a startup, as in research computing, you don’t actually know at any given time exactly what skills and technologies you’ll need in the coming years, and technology skills are only one piece of the puzzle anyway. He emphasizes having clear rubrics for hiring that also include questions around ego, adaptability, technical communication skills, and cross-functional collaboration skills.

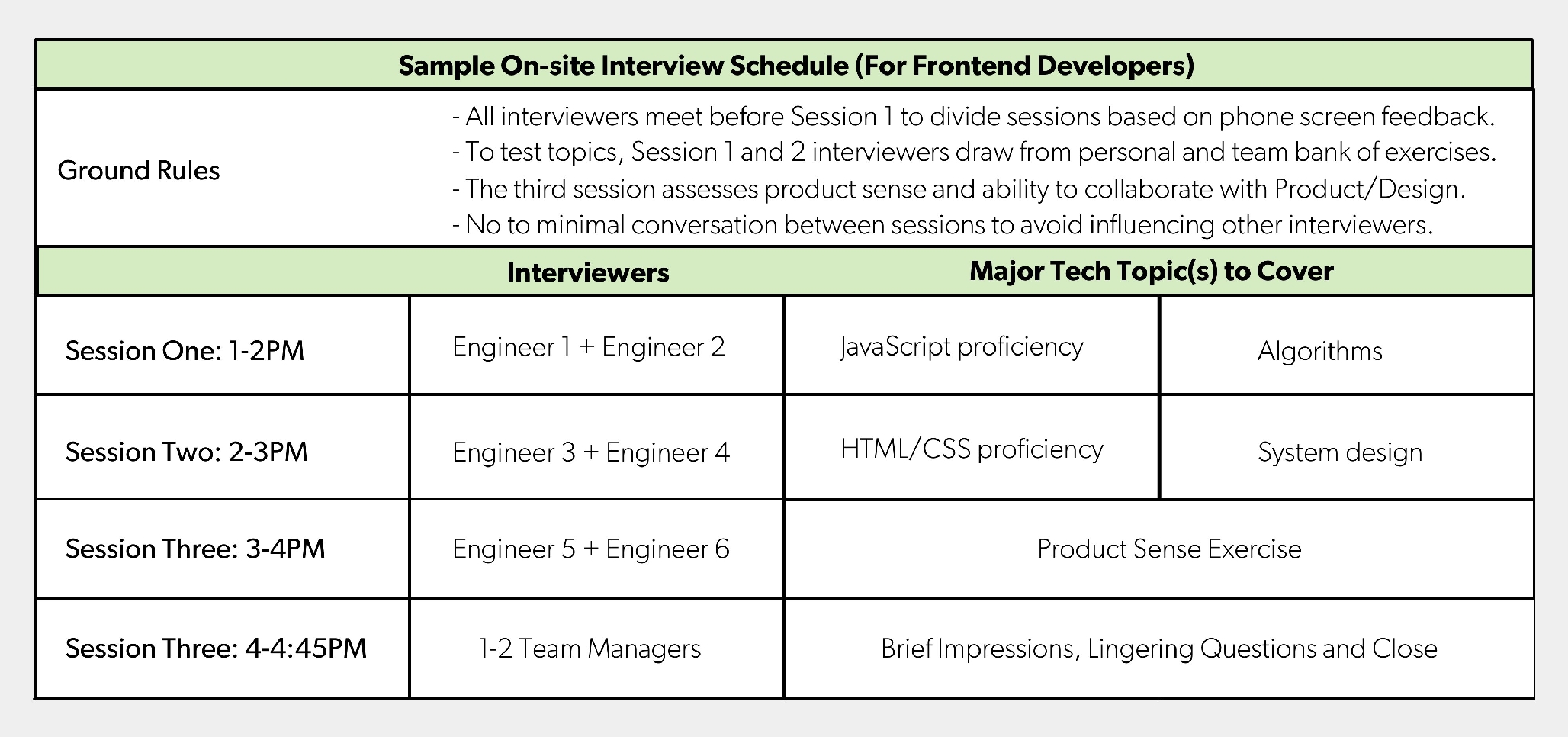

For running the interviews, he recommends having two interviewers at a time - it allows interviewers to split time between engaging and observing, it helps spot biases, and it helps train new interviewers. He also recommends having the entire team interview, partly to emphasize the importance of interviewing and to communicate widely what is needed for a successful new hire. He also recommends doing more interviews, bringing in ten for each position. Below is an example of how an on-site interview schedule would work for a front-end developer.

Post interview, he recommends having a huddle, getting an initial yes/no (Lever uses strong hire/hire/no hire/strong no hire) and then dig into they why’s to surface and amplify meaningful signal. Before the huddle, it should be clear who is making the decision, and how, so that everyone knows how their input will be used.

Larson’s article also emphasizes the importance of clear, team-wide definitions of goals and rubrics for what a successful hire would look like prior to interviewing - this time for managers or team leads. As we know, manager or lead are particularly tough jobs to nail down, and if you’re having trouble finding candidates everyone can agree on, this could well be why. He also suggests that if you start seeing some common reasons why interviewed candidates are poor choices, to push screening for those causes to phone screens.

Finally, Notion and GitLab have extremely detailed documents describing how interviewing works at those companies. Those are useful not only for us to learn from in designing our own hiring process, but as starting points for candidate packs for those we interview.

Staying Visible When Your Team Is in the Office…But You’re WFH - Dorie Clark, HBR

Look, in research we’re often pretty uncomfortable emphasizing our abilities or accomplishments. “The work should speak for itself”, we’re told. But that’s transparently nonsense. In 25+ years I’ve seen a lot of work, and not once has any of it pulled me aside and explained its significance to me, nor how it will help me achieve my goals. If your work speaks to you, take a vacation, and if it continues speaking to you, seek professional help.

The fact is, a number of us and our teams are going to be remaining distributed while our managers, stakeholders, and some of our peers go back to offices. And that means to stay visible and on our bosses and stakeholders’ radar we’ll need to have to be a little more intentional about being easy to work with, and for our teams outputs to be obvious. We might not like that, we may even find it distasteful - and, you know, too bad. If you won’t do it for yourself, then suck it up and do it for your team members, whose hard work individually and collectively deserves to be recognized.

Clark recommends:

Ten simple rules for teaching applied programming in an authentic and immersive online environment - Frances Hooley, Peter J. Freeman, Angela C. Davies, PLoS Comp Bio

This is a nice set of recommendations of teaching long-form courses online. The lessons come from the authors’ experiences teaching a masters degree and a postgraduate certificate in clinical bioinformatics in particular, but its recommendations should apply quite broadly to teaching researchers computing skills, and fall under:

When the “ten simple rules” format fails it’s because it degenerates into a laundry list (which perversely is much easier for me to summarize). Here it’s a very nicely put together and well thought out paper on teaching semester- or year-long research computing courses for researchers or practitioners, and if that interests you it’s worth reading.

Focus: assign multiple engineers to the same task - Dawid Ciężarkiewicz

We’ve talked here quite a bit - starting way back in #13 - about pull requests as asynchronous pair programming, and the benefits of pair programming - not merely for quality control but for knowledge sharing in both directions.

In this thought-provoking article, Ciężarkiewicz argues in favour of routinely having two (or more!) team members assigned to a task, so that rather than a code review at the back - or even before pair programming at a shared IDE would start - two people are bouncing the problem and possible solutions back and forth. The argument is that this leads to:

My take on research software development is that one of its defining characteristics is subtlety, rather than (in many other areas of software development) complexity - and thus having more input more often is important; so I tend to find Ciężarkiewicz’s argument pretty compelling.

What do you think? Have you seen research software teams routinely assigning pairs of team members to tasks? How did it go - what were the advantages and drawbacks?

Pre-Mortem: Working Backwards in Software Design - Seema Thapar, PayPal

We haven’t talked about premortems (#12, #43) in a while. If you don’t recall, the process - sometimes part of a project kickoff - is to have a well-posed project and then to ask the team to imagine that it’s finished, and it has failed. What has gone wrong?

Thapar gives us a particularly nice overview the why of premortems here, and describes how they’re run at PayPal. They start with a 1-pager describing the user story, get all the teams involved who would be involved with implementing it, and then asks them to suggest failure modes while the project is still nascent and can be shaped.

Thapar lists the advantages of such an approach:

She also gives a piece of advice I hadn’t seen: “Diverge before Converge” - solicit a wide range of feedback first, then start developing a consensus around priority areas.

It’s Time to Rethink Outage Reports - Geoff Huston, CircleID

Increasingly, private-sector systems provide their users detailed explanations of the reasons for unexpected outages, what was done to get things back up, and what they’re changing to prevent it from happening again.

As part of incident response, we should be routinely writing up similar reports for internal use, so that we can learn from what happened. With that done, it makes no sense to then keep our users in the dark! Most users won’t care about the details, but they will care that it matters to you to keep them informed and that you are visibly trying to improve the service you provide them in the future.

I guess we’ve become used to reading evasive and vague outage reports that talk about “operational anomalies” causing “service incidents” that are “being rectified by our stalwart team of engineers as we speak.” When we see a report detailing the issues and the remedial measures, it sticks out as a welcome deviation from the mean. It’s as if any admission of the details of a fault in the service exposes the provider to some form of ill-defined liability or reputation damage. To minimize this exposure, the reports of faults, root causes, and mediation actions are phrased in vague and meaningless generalities.

AWS Incident Response Playbook Samples - Frank Phillis, AWS

This is a handy resource - very detailed template playbooks for handing four kinds of incidents one might have running applications in AWS, and what tools you’d use in AWS to handle them:

It’s a GitHub repo, so hopefully we’ll see more posted over time.

The NSA Can Help Secure Your Kubernetes Clusters - Steven J. Vaughan-Nichols, The New Stack

Kubernetes Hardening Guidance (PDF) - National Security Agency

So this week, the NSA released a pretty easy to read, comprehensive set of guidance around securing Kubernetes deployments, and by all accounts it’s quite good. Vaughan-Nichols recommends reading it in full; he summarizes the sources of threats NSA concentrates on (supply chain risk, malicious threat actors, and insider threat), and a summary of the high-level areas the report concentrates on:

Nvidia Offers Hosted Large-Scale Processing for AI - Jeffrey Burt, The New Stack

Nvidia AI development hub now available to North American customers - Jonathan Greig, Zdnet

There’s a new cloud in town - NVIDIA is making LaunchPad, it’s AI-specific PaaS cloud built out of recently announced DGX SuperPods, available to North American customers. Since most of us won’t be buying a fleet of A100s any time soon, this is one way to start playing with that kit, as well as Fleet Command (kind of an AI-ops specific hybrid/multi-cloud scheduler/resource manager, it looks like?) and Base Command (which seems to be a way to put together individual ML jobs).

It’s not going to be cheap, though. According to Greig there’s a $90k/month, 3-month minimum investment involved, and I’m not sure what that includes and what’s extra.

50th International Conference on Parallel Processing - ICPP ’21 - 9-12 Aug, Virtual

A four-day conference covering everything from accelerators, embedded systems, parallel programming models, NVM, data structures, performance optimization, storage systems, and more.

25th Int’l Conference on Research in Computational Molecular Biology (RECOMB 2021) - 29 Aug - 1 Sept, Online, Free

RECOMB is a very selective conference featuring novel methods with implementations, typically focussing on high performance in some dimension (space, time). Scheduled are 3.5 days of very deep talks on algorithms and code.

27th International European Conference on Parallel and Distributed Computing (EuroPar ’21) - 30 Aug - 3 Sept, Online, 230€

The program for EuroPar ’21 is up, covering applications and algorithms, architectures and accelerators, ML, load balanacing and scheduling, power and performance modelling, programming languages, cloud and edge computing, and more.

Workshop on Sustainable Software Sustainability 2021 (WoSSS21) - 6-8 Oct, Online, Free

From the workshop page:

The overall aim of the series is to bring together participants from a broad range of communities that are interested in how to deal with software sustainability, primarily from the perspective of scholarly and scientific research. WoSSS provides a meeting place to identify and discuss the hurdles and challenges we are facing. After Open Access to publications and FAIR data, software as a research output worthy and in need of preserving and sharing is only recently receiving more attention from policy makers and research funding organisations. […] WoSSS21 is not only oriented to research software developers, researchers who code, and specialists in digital preservation and research infrastructure, but also to policy makers in open science, research funders, and others who want to learn about the issues at stake and who have something to contribute.

How to avoid shell injection vulnerabilities - avoiding catastrophe when a user submits arguments to a command to be run.

git checkout can be confusing for new users because it can be used to switch branches, restore file(s) to versions in the current branch, or set up a detached HEAD state to reference a particular commit. For the first two, more common, cases there are now specific subcommands - git switch and git restore - that can be used.

You can do better than “conn”; your database connection deserves a name.

Have you ever thought about writing your own time-handling library? Reason 3,871 you shouldn’t - leap seconds are exposing bugs by not happening often enough lately.

Accessibility considerations - when to use alt tags and when not to. While you should usually use alt tags, adding them to essentially decorative elements, or trying to shove huge swaths of text into an alt tag instead of including it in the body, doesn’t always help.

xeyes has been updated. It’s now at 1.2, if you’re curious.

Running an Amiga in 2021.

Getting started with writing a linux kernel module.