Hi, everyone:

I hope you’re doing well.

I’ve neglected the “managing your own career” section lately, which I’m going to try to fix; we spend a lot of time here talking about helping our team members develop their skills, which is good and we certainly have an important role to play there, but we have to look after our own careers as well. Luckily in the past week several very relevant articles have crossed my browser, and so I present for you this week an attempt to bring that back into balance a bit.

Are there particular things you’re doing to track your own career progress, or get ready for future next steps? Are their particular gaps you’re not sure how to address or questions about how to progress? Please feel free to email me at jonathan@researchcomputingteams.org or just hit reply, and I’ll answer as best as I can and with your permission ask the newsletter readership to chime in, too.

For now, on to the roundup:

A Manager’s Guide to Holding Your Team Accountable - Dave Bailey

A lot of research computing team managers - especially those of us who came up through the research side - aren’t great at holding the team accountable. It’s pretty easy to understand why - the whole idea of being accountable for timeline and scope is a bit of an awkward fit to that world. Something took longer than expected, or someone took a different tack than they had committed to earlier? I mean, it’s research, right? If we already knew how to things were going to go ahead of time, it wouldn’t have been research.

But supporting research with computing and data is a different set of activities, and to give researchers the support they need we need to hold team members accountable for their work, and team members need to hold each other - and you - accountable. Mutual accountability is what separates a team from a bunch of people who just happen to have similar email addresses.

So going from a role in one world to one in the other takes some getting used to. It’s easy, as Bailey reminds us, for accountability conversations to feel confrontational - maybe especially to the person starting the conversation. But he summarizes our role as:

In particular, he distinguishes between “holding someone to account” and “giving feedback”. Holding someone to account involves clarifying the expectations and asking probing questions about what happened; giving feedback means providing your reaction about what has unfolded.

There are familiar points here for longtime readers - Bailey includes discussion of the Situation Behaviour Impact (SBI) feedback model - but distinguishing between holding to account and feedback is useful and new, and the article is worth reading. Bailey also gives a helpful list of probing questions:

As well as some starting points for accountability conversations.

Secret tips for effective startup hiring and recruiting - Jade Rubick

How do you identify great engineers when hiring? - Yenny Cheung, LeadDev

These articles read together give a sense of what a really good hiring process could look like. Rubrick’s article starts well before the job ad goes out, and continues well past the hiring of any one candidate; it’s about strategy pipeline, and iterating. But it’s intended to quite a wide audience, so doesn’t go into the details of interviewing for a particular type of role, which is where Cheung’s steps in.

Rubick’s article starts very early on in the process. What is your hiring strategy? Why should someone work on your team as opposed to any of the other myriad of opportunities out there? What does your team offer, what can you be flexible enough or emphasize? A clear and well articulated set of reasons and benefits here can be used in a number of places - your careers page, how you recruit, where you post ads, and more.

Rubrick then recommends putting real thought into the job description and ad, testing the application process to see what it looks like, (he also has a nice article on creating an interview plan), and moving quickly.

A great idea I haven’t seen anywhere else is to start assembling useful information for candidates - like an FAQ, and which can be added to with real candidate questions - and when it’s big enough to be useful, to begin sending it to candidates as part of the process once they get through the resume screen stage. He also recommends giving feedback to and asking for feedback from candidates, keeping in touch with promising candidates, and actively recruiting based on everyone’s network.

Cheung’s article goes into the process of interviewing. She starts with some basics, like having clear expectations up front; having gone through the resume and detail and mining for questions; and staying away from hypothetical questions (I can’t agree with this enough; either have them do the thing and evaluate it, or ask them how they have done the thing in the past, don’t ask them to just make up how they might do the thing).

The secret sauce, in her estimation (and again, I strongly agree) is in the followup questions. If you’re not digging deeply into the answers with more questions, you might as well just have people email in their responses. Digging deep into the whats and hows is how you get the information you need to evaluate the candidate.

Dropbox Engineering Career Framework - Dropbox

We’ve talked a lot in the newsletter about career ladders, but it’s generally been for our team members - the path of increasing technical seniority. What about us? How do we know what skills we should be developing; how do we know if we’re making progress?

In our line of work career progression is slow and comes in fits and starts, but that doesn’t mean we can’t be levelling up our skills. Dropbox has an unusually clear engineering management ladder, starting with M3 (the link above) through a more senior (but still front-line) M4, through an M5 Lead-of-leads (Senior Manager), M6 (Director - manager of senior managers) and M7 Senior Director. It has plain language descriptions of what they expect to see - in terms of behaviours and outcomes - for leaders at each level.

Areas covered are the big picture scope/collaborative reach/impact levers (how you get things done), Results, Direction, Talent, and Culture.

Do those line up with what you’d expect a research computing manager to be or aspire to? What are the biggest gaps?

Writing is Networking for Introverts - Byrne Hobart

This is an older (2019) article that recently started circulating again, and I really like it.

Relationships are a key part of being an effective leader, and for building your career. Trust speeds collaboration, and we trust people we already know and have interacted with.

Increase the circle of people who trust you (and you trust) so you can have more effective and frequent collaborations requires building your relationship network. “Networking” has come to sound like a suspiciously disreputable process, especially to people like us in research, but it needn’t be. Meeting and interacting with other people who share our interests, and in doing so building professional relationships, is a good and healthy thing.

It’s also super hard to start doing if you’re an introvert, which many of us at the intersection of research + computing are.

Hobart encourages those of us who find in-person networking uncomfortable to think of writing as a way to build our professional network; as he points out,

As an example, you might want to start a blog or a newsletter. You know, hypothetically.

I’d add that in our work, giving a talks at conferences is another great way to speed networking for introverts. Once you’ve given a talk the rest of the mingling events at the conference are way easier to navigate. People come to you to ask questions about something you were interested enough in to give a talk about.

Timeboxing: The Most Powerful Time Management Technique You’re Probably Not Using - Nir Eyal

I’m a little surprised to see that timeboxing hasn’t come up on the newsletter as often as I would have thought - it was one suggested strategy out of five in one article we covered in #53. It’s a very useful technique for making sure you get things done, and for scoping those things.

Problem with a to-do list include:

Timeboxing involves actually blocking off time on your calendar to do certain tasks - or classes of tasks, and assigning items to any particular box. It’s great because it actually schedules you to do task X in an hour on Tuesday afternoon, meaning you’ve scoped it better than just a bullet point saying “X”, and by committing to that you’re less likely to be distracted during that hour.

Eyal cautions us to:

Easy Guide to Remote Pair Programming - Adrian Bolboacă, InfoQ

Bolboacă walks us through the how and why of remote pair programming, and InfoQ helpfully provides key takeaways (quoted verbatim below):

The points that stand out to me is that pair programming isn’t a good thing in and of itself, it’s a practice that can help you achieve specific good things; and you’re more likely to achieve the good things you want if you keep the goals in mind. Maybe it’s knowledge transfer and mentoring juniors, or a second pair of eyes on some particularly sensitive code, or being faster than waiting for a code review on a PR. Those are all great objectives, but they’re different, and how you roll it out the practice will affect how well those objectives are met.

Bolboacă also highlights areas where it’s not likely to work well:

FAIR is not the end goal - Daniel S. Katz

FAIR - Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable - is a term of art in research data, expressing requirements for how to make the data useful. There are a few talks and write-ups on “FAIR for software” out there, but as Katz points out, code is different than data; we want to be able to successfully use it, build upon it; it decays without maintenance in a way data doesn’t, and it should be robust for use in different situations.

We could stretch the Reusable definition a great deal from where it’s useful in data to where it’s meaningful in software, but at that point it starts to look so different, what’s the point?

Katz also thinks software (but not data??) should be citable and credit given to contributors.

The Developer Certificate of Origin is Not a Contributor License Agreement - Kyle E. Mitchell

There’s been some discussion lately of a “developer certificate of origin”, where a developer asserts where the code comes from and that they are able to grant a license to the project. It’s a simpler document, and avoids the more complicated contributor license agreement approach, so it’s attractive for small open source projects.

Unfortunately, as Mitchell points out, it falls short in not actually granting an explicit license, which greatly limits what the open source project can do with it. Maybe that’s good for your project, but it would hugely complicate re-licensing the project, even to an updated version of the same license (e.g. GPL 2→3).

Introducing PyTorch-Ignite’s Code Generator v0.2.0 - Victor Fomin, Quansight Labs

PyTorch Ignite, which just came had an 0.4.5 release, is a high-level library for the PyTorch - think Keras for Tensorflow, but newer (and so less mature).

Even with such libraries, for a lot of common workflows - computer vision or text classification - there is common boilerplate that fly off the fingers of those experienced in the field but that are a barrier to those getting started. Ignite Code Generator doesn’t really generate code so much as provide a set of templated starting points - think cookiecutter or similar templates - that let you set file prefixes, iterations and stopping points, checkpointing, logging, etc.

To be clear, my comparison with cookiecutter is meant as positive - these ready-to-go workflows are both extremely valuable and relatively easy to contribute (and to the Quantsight team’s credit they set up an extremely helpful contributing guide right from the start). Any effort which helps improve a research computing team’s productivity by reducing toil and tedium while increasing knowledge sharing is an effort I’m likely to support.

From Data Processes to Data Products: Knowledge Infrastructures in Astronomy - Christine L. Borgman and Morgan F. Wofford, Harvard Data Science Review

I’ve been thinking for a while that to get really complete description of a process involving people, you sometimes need to enlist an outsider, or find someone who’s very new to the process and the ecosystem it’s embedded in. Otherwise you end up with a situation like having children explain to a pretend robot how to make a peanut butter sandwich; steps that are “obvious” or so important as to seemingly go without saying just get omitted.

A couple of careers ago I was in astrophysics; observational astronomy has a long history with data and data sharing, and so I read this paper by Borgman and Wofford at the UCLA Centre for Knowledge Infrastructures with some interest. Actually - and I’m not proud of this - I read it with some initial skepticism of “outsiders” reporting on how astronomy groups handle data. But it’s a great overview, and I recommend it to others who aren’t in the field (or haven’t been for a while) who want to know how modern astroinformatics is done, current data practices, products, and infrastructure with the examples of a large project (the Sloan Digital Sky Survey) and two smaller pseudonymous groups.

Astronomy has a lot of advantages over other fields - a single 2-d sky (although there were bitter fights ending only fairly recently to get everyone to agree to a common coordinate system) to study at various wavelengths, no privacy concerns, and relatively common and structured file formats (although again the file formats were not an easy battle for the community). Even so there are a lot of challenges that practitioners will find familiar; the multiple roles of participants, both of which are pretty important, but only one provides recognition:

each member of the group has two roles: “one as a pretty independent scientist…and then [as] support [for] the general, larger project of the group…”

the issues of funding those maintenance and support activities:

“[Maintenance] tends not to be addressed, and it’s boring. … at some point you have to do it, you have to paint your house, you have to have the roof replaced, it’ll happen to every house. … it would be really great if the agencies would say, ‘Okay, we need to put money into keeping these going. What are your maintenance needs for the next three years?’ …[eventually] you’re on a legacy platform that isn’t supported anymore, or that has security holes a mile wide….”

the more general issues with funding long-term products (including archival data storage) with project-based funding:

Multiple commitments to house and maintain the data “all have finite lifetimes, and [they] haven’t figured out what to do after the lifetime ends”

It’s also interesting to see how far things have come over quite recent periods of time. The Sloan Digital Sky Survey started in ~2000, and - I had forgotten about this - it initially relied on proprietary software in their analysis pipelines, something that would be completely unthinkable for a major project starting today.

The paper ends with some recommendations, including (paraphrased):

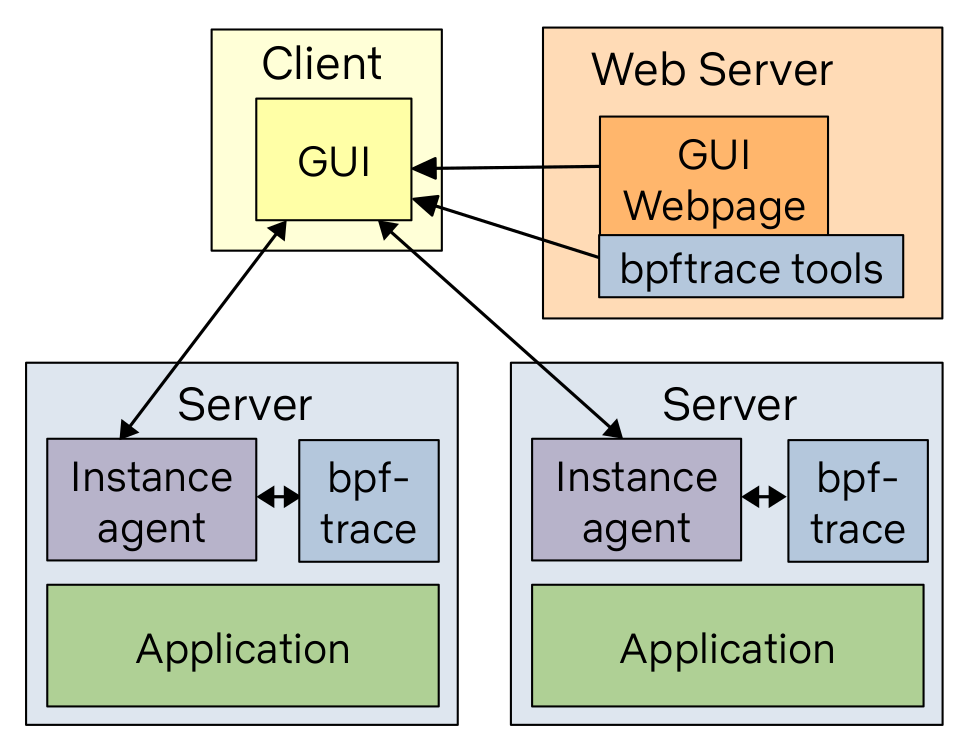

How To Add eBPF Observability To Your Product - Brendan Gregg

If you contribute to or maintain system monitoring software - and many systems teams do - this primer walks through the process of adding simple existing eBPF functionality - the example here is execsnoop, for reporting new processes by tracing execve() system calls - into your existing tools, along with giving suggestions for other tools and how best to visualize their results.

How the FPGA Can Take on CPU and NPU Engines and Win - Timothy Prickett Morgan

I’ve been doing this stuff for a while - 25 years now? Depends on what you count - and have been assured for most of that time that the age of FPGAs for general research computing was just around the corner.

As communities are gaining more and more comfort with dealing with different kinds of accelerators though and more diverse CPUs, handling the complexity of FPGAs starts to seem less farfetched than it did back in the day when Sun workstations and SGI boxes roamed the earth.

Morgan walks us through the recent history and the current state of FPGAs, looking at a particular vendor’s product (Xilinx’s upcoming Versal units) as a concrete example. With increasingly large numbers of complex “hard blocks” (I/O controllers, cryptographic engines, ports, etc) already supplied on-socket, there are more batteries included then there used to be - and with high bandwidth memory and fast interconnects available, sending enough data to the FPGA to be worth the effort of crunching on it there seems increasingly plausible.

Programming these devices remains challenging, and that is going to be the bottleneck - but as we saw with “GPGPUs” back in the day, once the devices get powerful enough, some pioneering research computing teams will start doing it successfully and showing others a path towards productive adoption.

SIAM Conference on Parallel Processing for Scientific Computing (PP22) - 23-26 Feb, Submission 14 Sept for contributed lecture, 1 Oct for Proceedings

SIAM PP is a big conference for parallel computing in science, with topics ranging from compilers and programming systems to algorithms, simulation + ML, uncertainty quantification, reproducibility, tuning, and more. It’ll be held in-person in Seattle this year. Instructions for submissions can be found here.

Phys. Rev. Fluids posted a thoughtful editorial policy on publishing machine learning papers - “We suggest that when ML is integrated in such efforts, there are at least three important aspects to address: (i) the physical content and interpretation of the result; (ii) the reproducibility of methods and results; and (iii) the validation and verification of models.”

In which someone on the internet says bad things about xargs, which is wonderful so he must be wrong.

An overview of DNS resource records - like A, CNAME, MX, etc. All 80 of them.

“In my day, we coded WebAssembly by hand”.

An argument that now, with webassembly, virtual file systems, GPU access, and raw TCP and UDP connections, the browser is the universal virtual machine which finally lives up to the promise.

CBL-Mariner, Microsoft’s internal Linux distribution (that is still so weird to type).

Writing your own Bash Builtin and loading it with “enable”. I don’t think I knew you could do that.

The seven different timers in curl and what they mean. Useful if you use curl to benchmark things or debug latencies.

Figuring out how mesh VPNs work by writing a simple one.

Cute visuals for explaining the various flavours of JOIN.

Examples of more realistic workflows for performing complex SQL queries using R.

A nice overview of Python 3.8’s protocol types, arguably formalizing an idea that’s been in Python since the beginning.