Hi, all:

I think I helped a team find the courage (and the organizational support) to say “no” to things this week.

Strategy for research computing teams is hard. I’ve sort of given up on trying to find strategy articles for the roundup that are suitable for us; most are for either large organizations with many moving parts which make no sense in our context, or for tech product strategy. The product strategy ones start off okay, but they really imagine being able to pivot products to very different markets, and that doesn’t work well for our super-specialized tools. We’re not normally going to be able to take an unsuccessful piece of software for geophysical applications and pivot it into a digital humanities platform. We work as part of the research “market”, not outside of it, and “finding product-market fit” for our individual products isn’t the problem.

The best articles I can find are for consultancies or for nonprofits or even new PIs, where the advice is the same: find a niche at the intersection of (things your team can excel at) and (things that are needed and not provided well elsewhere), focus relentlessly on that, and shift or expand focus only reluctantly and judiciously. Crucially, the niche should almost certainly not be an internally focussed, technical one (“javascript development”, “storage systems”) - like I said last week, nobody cares about your tech stack - but an externally focussed, researcher-problem one (“build applications for social sciences data collection”, “support for research data management plans”). We do want to find product-market fit, it turns out, but the product is our team, not a particular output.

With a little care you can handle a portfolio of such niches — it muddies communications a bit, but it’s certainly something that I see teams manage. But having none, or too many, makes success unreasonably hard. The one thing that all strategy discussions have in common is that a successful strategy is defined in part by what you won’t do, by what you choose to be out of scope. Absent clarity on that, no one knows exactly what you do (in any language they care about), and the typical failure mode in that case is trying to be all things to everyone. In that case you end up doing poorly at some of those things, soiling your reputation, and starting a vicious downwards cycle.

In this week’s case, an external team asking me for advice had been struggling for some time with a lack of clarity of mission. It was clear to literally every observer in what area the team was most successful, and where there were modest growth prospects, but culturally and organizationally the team felt it needed to accommodate every single request that came in, especially when money unexpectedly became tight. The result was flailing, high staff turnover, a wildly uneven reputation, and a larger organization that didn’t know what to do with it.

What they needed wasn’t a flash of strategic brilliance, or marketing genius. Literally no one was surprised by the outcome. It just took the pedestrian, labour-intensive work of making explicit that internal and external consensus around what the team should focus on, and building a consensus around what it was ok for them not to do. That meant re-casting what was the right scope several times, finding the right language to pithily summarize the scope, and pointing out the struggles (and duplications!) of trying to do work outside the scope. None of this was rocket surgery, it just took time and conversations.

Supporting research and your directs by being a professional steward of a research computing team isn’t easy, but it is simple. It is being deliberate about what you and your team are doing, and learning from what you and others have done.

Anyway, on to the roundup!

Hybrid Work: How to Get Ready for the Future of the Office - Mara Calvello, Fellow

We’ve all learned how hard it is to manage distributed teams in the past year. But most of us (hopefully) are going to moving to some kind of hybrid distributed/on-site work configuration when things come back, and by all accounts that hybrid mode is even harder. It’s really challenging to not have the distributed team members feel out-of-the-loop compared to on-site staff, and for on-site staff not to cut corners (documenting decisions and designs, etc) that we’ve learned are needed for distributed work.

The main thing now is to figure out (with team member input) what things will probably look like in the first instance, and start deciding what will be needed to mje that work. Calvello goes through three models:

(FWIW, our team will land somewhere between remote-first and office-occasional). In either case, she then talks about some of the work that needs to be done - the bits most relevant to our teams are:

Research: Dispersed Teams Succeed Fast, Fail Slow - Marie Louise Mors and David M. Waguespack, HBR

Fast success and slow failure: The process speed of dispersed research teams - Marie Louise Morsa and David M. Waguespack, Research Policy 2021

As many of us consider a continuation of distributed teams post pandemic, some research suggests an issue I hadn’t seen before with distributed teams - they may be slower to admit that an effort failed and to move on.

In a study of 5250 already-formed research teams in particular, Mors and Waguespack found that given that the team existed and was successful (not a gimme!) the dispersed teams were already pretty good at working together and required less coordination and iteration to arrive at success:

In general, dispersed teams spent less time and went through fewer iterations before reaching success than the co-located teams. This suggests that team members are aware that it’s difficult to coordinate when they are located in different organizations ..

On the other hand, throwing in the towel took much longer:

Additionally, it may also be that it’s when failure occurs that the coordination costs kick in: Research also suggests that dispersed team members may find it more difficult to communicate around a failure or reach agreement on when it is time to abandon the project.

In the HBR article, the authors suggest a couple of interventions to prevent teams getting stuck on half-failed projects for a while - either more rigorous up-front screening to weed out projects less likely to succeed, or sync-ups or management intervention to flag that success doesn’t look likely and move on.

Increase your hiring success with job success profiles - Rod Begbie, LeadDev

TinyBird Tech Test - Javi Santana, TinyBird

This sounds like how hiring works at most of the research computing teams I’ve seen:

I’d seen enough job postings in my life to know you just had to come up with some qualifications (‘BS or equivalent in Computer Science’, ‘5+ years experience with Python’, maybe even a cheeky ‘Ability to work both independently and as part of a team’), throw them into a bulleted list, and start picking the best candidates from the resumes that will surely flood in

It’s hard to know if someone will be a good candidate for a job if you don’t know what success will look like for that role. Most people involved in the candidate selection and hiring process probably have a half-formed implicit idea of what that would look like, but they’re probably different. Unless it’s written down, it won’t be well though-out, agreed upon, and applied consistently.

Begbie suggests having clear primary objectives for the job, secondary objectives, and success indicators for 30 days/90 days/6 months/12 months. Not only does this clarify things internally and greatly increase the odds that you’ll be looking for the right people, by putting this information in the job ad you’re much more likely to attract candidates who actually want that job.

Relatedly, once you have a success profile it’s much easier to understand how to evaluate against that profile when you’re interviewing. Santana provides one real take-home problem they use at TinyBird, a company that builds real-time data processing tools. It involves writing up how you would solve a data ingest-plus-expose-an-API problem, and describes the rubric they use to answer it (it’s almost all about the communications, not the technical beauty of the proposed solution).

An Open-source Wish List - Matt Hall, Agile*

How reproducible should research software be? - Sam Harrison, Abhishek Dasgupta, Simon Waldman, Alex Henderson, Christopher Lovell

Hall ponders minimum requirements for scientific code, particularly around reproducibility, and comes up with a prioritized list:

There’s a longer checklist but that’s the gist - he then directs readers to the paper by Harrison et al which defines four levels of reproducibility:

What I like about these is that they suggest a graduated approach - that not all code is infrastructure and so doesn’t need the full arsenal of tools deployed. Hall’s is nice because it starts off very approachable, and readers will know that I very much like the technological readiness model that Harrison’s resembles.

Introducing Developer Velocity Lab – A Research Initiative to Amplify Developer Work and Well-Being - Alison Yu, Microsoft

In #66, we talked about an article, “The SPACE of Developer Productivity”, looking at Satisfaction, Performance, Activity, Communication/Collaboration, and Efficiency of the work environment of developers at an individual or team level, and how these were key for developer satisfaction.

It turns out that was the first publication of Microsoft Research, Microsoft Visual Code, and GitHub’s new Developer Velocity Lab, a cross-organization team aimed at improving software developer’s productivity, community, and well-being. It’ll be interesting to see what comes out of this group.

Putting out the fire: Where do we start with accessibility in JupyterLab? - Isabela Presedo-Floyd

We’re kind of rubbish at accessibility of research software. This article by Presedo-Floyd spelling out what needs to be done for JupyterLab gives some idea of the scope of the problem for a big piece of software like that; luckily there is a sizeable community there of people willing to help. Lots of other crucial pieces of research software don’t have that kind of community.

I think on the whole the accessibility of command line software is probably better, but I know so little about accessibility that honestly I could have it exactly the wrong way around and I don’t even know where to look for information on that topic. Are there any groups out there doing accessibility for research software? Would love to hear from you.

Right now, the data-management side of articles in this section are preferentially about databases and their performance, which is an important but pretty small piece of research data management. What sites and feeds should I be looking at to get a broader range of data management articles - curation, archival, governance, and the like? If you have suggestions, send me an email and let me know.

How to Accelerate Your Presto / Trino Queries - Roman Zeyde

How to Interpret PostgreSQL Explain Analyze Output - Laurenz Albe

Two articles on improving query speed using EXPLAIN ANALYZE in Presto and PostgreSQL. Presto is a new-ish and interesting tool that can query many different data stores (including Postgres, mysql, mongo, and columnar data formats like parquet).

High Performance Ethernet: to IB or not to IB - John Taylor, Steve Brasier, John Garbutt, StackHPC

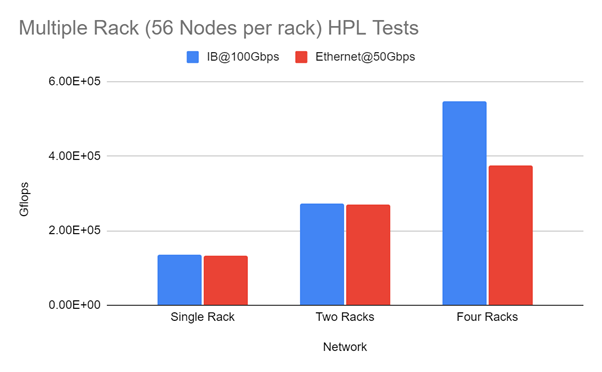

We talk about increasingly high-speed ethernet here relatively frequently (e.g. in #74); what’s interesting isn’t the speeds and feeds so much as the fading distinction between ethernet and specialized networks like infiniband. As modern ethernet reaches these speeds, support RDMA, and drop latencies - but can still support things like VLANs - at what point does infiniband stop mattering for medium-sized systems? For large systems?

Taylor, Brasier, and Garbutt look at ping-pong and HPL tests with 100Gbps IB and 50Gbps RoCE, and find that it’s essentially a wash for one- or two-rack systems, and it’s only at 4 racks that there’s a huge win for IB. In the author’s view, there are still issues particularly around congestion management, and IB still has better hardware offload for global reductions.

Amazon ECS Anywhere - Massimo Re Ferre, AWS Containers Blog

Amazon FSx for Lustre Now Supports Data Compression - HPC Wire

AWS has a couple of additional features in some of their services which might be of interest.

The first, ECS anywhere, allows you to use ECS (their container deployment and control plane functionality) to manage container workloads in other clouds or even on-prem. You run an open-source container agent on your own system - Linux or Windows, someone on twitter who I can’t find now posted that they got it working with Ubuntu on a Raspberry Pi - connect that agent to your ECS, and you can launch containers from AWS.

This is pretty transparently a way to help with hybrid applications or to enable “bursting to the cloud” easily, but it’s pretty cool and I think it means you could use the increasingly interesting looking AWS Copilot to create and manage web applications on your own systems.

The second is of interest to a different audience - Amazon’s managed Lustre file system now natively and transparently supports on-the-fly compression using LZ4. I would love to see benchmarks of resulting performance and storage cost changes for some different kinds of research computing workloads.

File Permissions: the painful side of Docker - Alexandros Gougousis

Docker host bind mounts, or even just copying files into the container, can be finicky, especially when you try to do the right thing by running the processes in the container as a non-root user. Gougousis walks through the basic issue - since everyone shares the same kernel, UIDs/GIDs in the container has to correspond to UIDs/GIDs in the mounted file system - but user and group names are not automatically the same (unless you use root, which you shouldn’t). This issue shows up typically as file permission issues, which “look” fine when looking at usernames vs UIDs.

He walks through a few options for solutions, including manually mapping usernames to UIDs, using ACLs, or user namespaces.

Correctness 2021: Fifth International Workshop on Software Correctness for HPC Applications - 19 Nov (part of SC21), Papers due 9 Aug

A workshop on correctness in HPC software; topic areas include

With spot instances, you have to be ready to lose the node - but in practice they can be extremely long-running, and being ready to lose your node at any time makes for very resilient practices. Here’s an example of using external services to run spot instances for personal servers.

Building a vim clutch pedal for speedy editing. Vroom!

A twitter thread on fixing a keyboard “bug” and the 40 year old history behind it.

Docker-slim looks like a pretty cool tool to reduce docker image size while generating a security profile.

File descriptor limits, or don’t use select(2).

If your team does a lot of github automation, you might want to consider using a Github app and Vault to generate ephemeral keys rather than reusing a service account’s credentials.

A tutorial from our colleagues in digital history on the very helpful JSON Swiss-army knife, jq.

A good overview of MySQL storage engines.

Uber has a promising looking open-source time-series Bayesian prediction tool, Orbit.

Two new front-end tutorials - Learn CSS and an interactive tutorial to DOM events.

A lovely interactive tutorial on the CSS z-index and stacking contexts.

Navigating your filesystem too boring? rpg-cli turns every cd command into a move in a rogue like game. cd ~ — if you dare.