Hi!

So you’ve got a list of hiring requirements written up - the next step is to think about how to evaluate candidates against the requirements. That’s next, or you can skip ahead to the roundup.

Once you have a pretty clear list of job requirements and a sketched out job description that the team members and other stakeholders have agreed on, the next step, before even a job ad, is to figure out how you will evaluate candidates against the job description.

I’m writing as if it’s a linear process - define requirements, then figure out evaluations - even though it’s much more likely to be iterative. A requirement has to be clearly defined enough to be relatively straightforwardly and unambiguously evaluated, for you and the candidate - that’s one of the main purposes of the requirement! - and it often won’t be right away.

A clearly defined requirement will immediately suggest some methods of evaluation. “Tell me about a time when you debugged a service outage on a linux server under time pressure” is a good and interesting interview question. “Do you have intermediate linux sysadmin skills” isn’t. So as you start figuring out evaluation approaches, some of the job requirements will be sent back to the team for clarification.

As with the description itself, putting together first version yourself and then collecting input from the team members and stakeholders the new person would be working with will help you put together a better process, and make sure those who are asking the candidate questions will be thinking along the same lines.

The fact that we’re looking for reasons to say no against our carefully-selected list of requirements and activities means a couple of things:

For 1, evaluation, post evaluation those involved should be able to quickly make a firm decision about whether the candidate proceeds to the next step. Whether a technical screening, a short screening interview, or a longer interview, team members should be keeping track against the list of criteria you’ve agreed upon. For us, for instance, for a current position that might look like:

“Cultural fit” and soft skills for working our team:

Technical skills:

If there is evidence of a significant deficit in any of those skills, that’s evidence that they are not going to succeed working on our project and it won’t be a great match for them or us. If they could succeed with that deficit, it means we’ve defined our requirements - or our definition of success - incorrectly. If they have those capabilities and don’t succeed anyway, it means we’ve missed something.

For 2, no non-disqualifying questions — this is why even Google doesn’t ask puzzle questions any more - why are manholes round, how many ping-pong balls fit in an airplane, etc. Questions that hinge on having some key insight during the stressful, artificial, and time-limited period of an interview - just aren’t helpful. Them not getting the answer doesn’t tell you they can’t do the job, so there’s no point in spending precious interview time asking it.

This also really limits the scope of technical questions you can usefully ask and expect answers to in real time. If they need some particular fact in their head, or to see some key insight, or it’s just too much to pull off in a stressful hour under artificial conditions, it doesn’t disqualify them from the job, so doesn’t help you make your decision. We know that live coding interviews test for confidence more than coding ability.

There are technical questions which work well live, or as “take home” assignments, and we’ve tried to define the technical requirements above so that some of them lend themselves to simplified versions of the tasks they would be doing every day, E.g., “here’s some back end code that implements a simple API. Walk me through it; you can ask as many questions as you like”. Or “here’s a simple repo with an issue; submit a PR to fix the repo”. Or “here’s a simple repo with a PR; provide a review with the PR”. Other teams have had good luck with pair-programming a PR for an issue.

You want it to be hard enough to be in some way representative of the work, but simple enough that not completing the task adequately in some short amount of time genuinely is evidence against the hypothesis that they have the skill. Setting that level just right takes some calibration - that is, some experience - but the fact that you’ll improve questions over time is a good thing, not a bad thing, and it doesn’t absolve you from trying to ask the question even when you’re first starting to interview for the position.

These simulation-based testing of requirements can work for very technical skills, in small doses. Lots of fields do them - accountancy, for instance - and they can be useful! But we over-rely on them in computing. It reduces “making an assessment of a candidate ”to the more-comfortable-for-tech-people task of “making a technical assessment of code/architecture diagram invented on the fly”. Whatever tasks you use they’re going to be poor simulations for the day-to-day research computing work, so it’s not as dispositive as you might think. Worse, in the end, there’s only so many technical skills you’re going to be able to test in an interview, or so many take home questions a candidate will be willing to answer.

Luckily, you aren’t limited to what they can do in one or a few hours - you have all the accomplishments of their entire career you can dig into! So the meat and potatoes of any interview, even a technical one, rather than a simulation-based competency assessment, is going to be a behavioural interview; “tell me about a time…”.

You want to ask questions that probe the skills and behaviours you need. Hopefully the requirements you’ve defined are clear enough to lend themselves to this. Honestly, going through all your requirements and asking “tell me about a time when [you demonstrated requirement X]” is a pretty decent starting point for planning an interview, if you’ve got your Xs in order. Also note that behavioural interview questions can be extremely technical, if “requirement X” is a technical one! When you’re asking behavioural questions, the key is to dig into the answer a lot. Every time they make a decision in the story, politely interrupt and ask why; really dig down.

This is absolutely vital. Even if the story they’re telling is a huge success, if they can’t convincingly describe why they made one choice over another, it’s unlikely they’ll be able to repeat the success. And of course if the story is a huge failure but the decisions were reasonable given what they knew, and they’ve demonstrated they can learn from it, the story needn’t be disqualifying.

We’re getting pretty close to the end of the hiring series - we’ll talk next week about the actual interviewing process and setting up a pipeline.

Getting Over Your Fear of Giving Tough Feedback - Said Ketchman, The Introverted Engineer

Research: Men Get More Actionable Feedback Than Women - Elena Doldor, Madeleine Wyatt, and Jo Silvester

We’re people who went into both research and computing, and so as a population we are disproportionately task-focussed and introverted. That can make giving negative feedback - especially about work practices, maybe less about work outcomes - deeply uncomfortable. And humans avoid doing things that make us uncomfortable!

But your team members deserve to know when something they’ve been doing doesn’t meet your expectations. You wouldn’t want your boss to to keep feedback from you if there was something they thought you could do better, and it’s unfair to do the same to your team members. You’d want them to communicate it with kindness, but with clarity. Ketchman talks about three steps in getting over the discomfort of giving tough feedback:

Having a ready-made formula for giving feedback can be a huge help for this. Whether it’s the Manager-Tools feedback model or the very similar Situation-Behaviour-Impact model, it helps you give a structure you can practice on while keeping the purpose - improved future outcomes - in mind.

Building trust of course comes from regular one-on-ones, and from holding up your end of responsibilities when you’re asked to do things for your team member.

There’s an equity reason to get over discomfort about giving corrective feedback, too. Doldor, Wyatt, and Silverster looked at feedback given to 146 mid-career leaders, provided anonymously by more than 1,000 of their peers and managers and fount that corrective feedback was given less to women, and even positive feedback was given in a more fuzzy way that is harder to translate into concrete next steps. This was true of both men and women bosses of women. The more comfortable we can get giving concrete feedback, positive and negative, to all our results, the better they’ll be able to grow and develop. It’s not fair to let team members repeatedly fail to meet our expectations and stay silent about it just because we’re uncomfortable bringing it up.

Coaching and Feedback Tools for Leaders - Ed Batista

Batista has a list of resources he’s written or found helpful on the purpose and delivery of feedback and coaching. Manager-Tools Basics is very good on this, but getting another perspective is helpful.

How your organization’s writing reveals its problems — and potential fixes - Josh Bernoff

As written, asynchronous communication becomes more and more important to our teams, the first goal was simply to move conversations to async written format. Now that we’re settling in to this mode, it’s good to take a look at the documents your team is generating and see if they can be improved.

I don’t think the issues Bernoff identifies are necessarily symptoms of the problems he suggests, but they are areas that could be looked into - and those problems with the documents could be usefully addressed (with feedback!) at any rate. A few that struck me:

Templates for Writing a Better Board Report! - Dolph Ward Goldenburg

Research computing leadership can and should learn a lot from nonprofit leadership. Research computing grant-writing is are more like writing for nonprofit grants than it is for research grants (remind me to write this blog post some day). Managing open-source contributions is exactly managing volunteers. Stakeholder management, community outreach… there’s a lot of overlap.

This particular blog post won’t be relevant to all research computing managers. Some of us have mangers who are themselves involved in research computing, who because of their role keep track of the details of our work. Say, you’re a Manager, Research Software Development and you report to a Director, Research Computing - this article might not be relevant to you.

But if you are the technical lead of a project, and you report to a Scientific Advisory Board, either as their direct report or as an important source of stakeholder input. Then it can be very useful to think of that relationship as you heading a nonprofit and reporting to a board, and a lot of advice about keeping that relationship healthy and useful both ways carries over very nicely from nonprofit leadership.

If you’re meeting with your SAB monthly or quarterly, it can be hard to pull your head up out of the weeds and think about things they care about. If you talk too much about technical or team management details, at best you’ll bore them, and at worst they’ll decide to start directing you on those topics. (And why wouldn’t they? You’re the one bringing it up to them!)

Goldenburg has a board report template (in slides or a document) for like a two page regular report

The first topic and the last two in particular are genius - it primes the board members to be focussed on the big picture, and it lets you get feedback in the areas that you really care about getting input from them.

A Cloudy Future - Craig Nicholson

Open Data Cloud Still Problematic, says ex-Commission lead - Craig Nicholson

Repository of Broken Dreams - Fritz Sager, Johanna Künzler and David Kaufmann, Research Professional News

A decade or so ago, much was made of the dearth of publication of negative results. Journals don’t encourage it, the submission/review process is too onerous for such a small benefit in what could only be a low-tier journal, and so it doesn’t happen - even though negative results are data too, publishing such results would mean others don’t follow down the same dead end, looking for results in a way that can’t possibly produce them. A lot of discussion resulted; nothing really came of it, but at least it is recognized as an issue.

Uncomfortably, like experiments, most research computing projects don’t end in success. How could they? We’re trying new methods, new approaches, in an area that hasn’t been studied before. As the old joke goes, if we knew what we were doing, it wouldn’t be research. Software may just never work, or may never be useful to be adopted; infrastructure may get used grudgingly if at all, and abandoned at the first available opportunity; curated data stores may come together just in time for the field’s needs to change radically.

Research culture’s adamant conviction that management is not an area worthy of spending effort or energy learning or teaching means that we get precious few case studies of how research projects, and research computing projects in particular, went. So no one gets to learn from previous research computing project or product management work unless they were actually part of it.

And our cultural aversion to publishing negative results in particular means when we do read such a case study, it’s of a self-congratulatory, “here’s how we did it!” nature - a handful of one-offs here and there, with no way of judging whether things claimed in retrospect to be key for projects A or B truly were or or not, much less whether those lessons are generalizable. Frank post-mortems are few and far between.

So with this in mind, forgive me for saying that I can’t get enough of these stories of the European Open Science Cloud or SystemsX.ch.

Research data management has been seen to be a coming issue from some time. With no easy mechanisms or encouragement to discover or share data, re-use of expensively collected research data occurs far too seldom. From the first article if Nicholson’s:

The EU-led European Open Science Cloud is supposed to change all that. Its founders’ grand plan was to create a way for researchers to securely share results, find other data and play around with a multitude of standardised datasets, bringing together a variety of existing infrastructures and combining them with data-crunching services in a one-stop shop.

About about €250 million(!) has been spent since 2014(!!), with little coherent to show for it, and as a result, in 2020 a league of european research universities has taken over some governance duties for EOSC to reboot the effort:

“We have a concept, an ambition, some building blocks in place, but a huge distance still to travel to make it a reality,” says Paul Ayris, pro vice-provost of library services at University College London…. Looking back at six years of work on the cloud, he says, “We’ve made a good start.”

I still have yet to see a proper post-mortem for what went wrong. From the articles, it sounds like it was a project with a large number of initiatives and institutes stapling together a bunch of semi-related efforts with some narrative about how they were each integral to a coherent whole. They made large promises, but things never really cohered into a unified project plan aimed at serving research customers.

Crucially, EOSC in the future has to make other projects want to use it: again from the Nicholson article,

Ayris is “reasonably confident” of securing more EU funding, but says it’s challenging that the project has to bid for funding rather than having its own budget. “It’s a big job for the EOSC to be inserted in all those project bids,” he says.

This is absolutely key, and why I’m not against large research computing projects needing to have a sustainability plan. If researchers wouldn’t value the project’s contribution enough to write it into a grant, then how important is it exactly that the project is undertaken in the first place?

Sager, Künzler, and Kaufmann, who wro write a similar story about SystemsX.ch, a nearly-as-expensive (€204m) Swiss effort over a longer time (2009-2018) that included both funding systems biology projects, and buliding centralized storage, datasharing, computing and data science support for systems biology data (SyBIT). The idea seems to have been to bring existing expertise together, strengthening both collaboration between groups and establishing a large Swiss presence in the field.

The centralized resources, however, seem to have gone largely unused. What SyBIT built was not something users actually wanted to use, and without the data the central repository was useful. Technically, interoperability between various data formats was much more challenging than implementers had originally imagined. As with EOSC, lack of coherent governance was lacking. Personality conflicts emerged, and voluntary cooperation between the competing and mutually distrustful institutions involved wasn’t enough to align activities.

Sager, Künzler, and Kaufmann, who wrote a journal article going into more detail, make three recommendations, which unusually I quote in full here:

First, a feasible project design is crucial. Failings here cause problems down the line, such as user resistance, non-compliance or technological complexity. Any realistic project design should incorporate researchers’ expectation of autonomy. Second, a project’s top-down and bottom-up governance need to be well balanced. Research infrastructures are shaped by an ongoing interaction and feedback between those who run them and those who use them. Large-scale research programmes must take their target group seriously and consider their needs in the design and implementation phases. Third, those planning research infrastructures should take context seriously. There is no one-size-fits-all model for developing a large-scale research programme. The project must take into account its political context and other potential factors at all stages. Success depends on it.

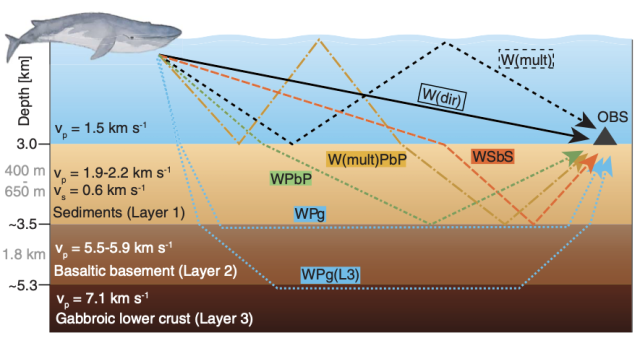

Seismic crustal imaging using fin whale songs - Václav M. Kuna and John L. Nábělek

This made Ars Technica, so you probably already saw it, but.. c’mon. It was known that seismometers could pick up whale song; seismologists Kuna and Nábělek discovered that you could actually do seismology with fin whales’ 20Hz song, both tracking the whales and using this naturally-occurring sonic source instead of or at least complementary to the use of disruptive explosive charges or air guns.

Snowflake retros - Mike Crittenden

While retrospective meetings are useful for all kinds of research computing work, software development is main area where retros happen so often and regularly that they can start to get stale.

Crittenden suggests avoiding that by making each one unique - setting up a rotation of both the person who runs the retro and the format of the retro (there’s a link to 10 different retro formats) to have them regularly changed up.

As a postscript - I can not recommend highly enough the approach of having team members rotate through running regular team meetings. Builds an important skill in your team members, makes people more willing to take charge of things, you get additional perspectives, etc.

Time Travel Debugging for C/C++ - Markus Woschank

Research software development isn’t generally particularly complex, but it’s often fiendishly subtle. (To my mind, that’s why typical software engineering processes aren’t particularly well suited to research software development in the early stages of technological readiness - proof of concept and prototyping - because those are built around managing and containing complexity, and do little to hep with subtlety).

So sometimes we need extra support in observability into the software’s behaviour and in debugging same. Woschank gives a quick tour of time-travel debugging for C/C++ code with gdb and rr (and WinDbg, if that’s your thing). He also offers a a suggestion from rr that I hadn’t heard before - enabling time-trace debugging in CI setups to speed debugging CI failure.

PCI-Express 5.0: The Unintended but Formidable Datacentre Interconnect - Timothy Prickett Morgan, The Next Platform

This is a nice history of PCI-Express, and how recent development PCI switches for PCI-Express 5.0 starts to make an interesting case for PCI going off node and making for a datacentre interconnect. There’s too much for me to distill here; if you’re interested, the article is a good read.

Slack’s Outage on January 4th 2021 - Laura Nolan, Slack

A lot of us noticed Slack being down for several hours on what was for many the first day back after the holidays. A good incident report always is worth reading, and this is a well-written overview going deep into the stack to explain what went wrong.

Like many incident reports posted here, this drives home a few points:

Open Source Update: School of Software Reliability Engineering (SRE) - LinkedIn Engineering

LInkedIn has updated its School of RSE materials for new hires or those looking to move into SRE. Even if your systems team isn’t thinking about moving to FAANG-style SRE operations, the basics covered in the material cover a nice range of dev-ops style development, deployment, design, monitoring, and securing of web applications.

The Twizzler Operating System - Center for Research in Storage Systems, UC Santa Cruz

This is here not as an example not of a new OS you should keep your eye on - it’s a research project - but as example of the sorts of changes that persistent memory might have not just on storage but on how we think about compute. If NVM becomes common - especially with DMA - and memory and storage systems stop being distinct, then a lot of assumptions that went into current OS models start looking weird.

Twizzler is what happens if all of these thoughts are followed to their logical conclusion. Inevitably the future of computing won’t look like all of the changes Twizzler is making, but I wouldn’t be surprised if one or more aspect of Twizzler looks prescient a couple decades hence.

Argonne Training Program on Extreme-Scale Computing (ATPESC 2021) - 1-13 Aug, Chicago - Application Deadline 1 March’

Competitive applications are open to this 2-week program. Eligibility criteria are here; notification by 26 April.

Bioinformatics Open Source Conference - 28-30 Jul, Abstracts due 6 May

BOSC is a broad and well-received conference on open source bioinformatics. Due date for 1-2 page long abstracts is May the 6th. Abstracts are prioritized that have

Research On the Go - Peter Schmidt, Mark Turner, Adrian Harwood, SORSE Panel Discussion, 18 Feb 14h00 UTC, Free

In this SORSE panel discussion, Schmidt, Turner, and Harwood describe moble apps for research, whether the apps are for researchers themselves, for clinical and educational research, or citizen science applications.

MGARD: Hierarchical Compression of Scientific Data - Ben Whitney, Supercomputing Fronteirs Europe 2021, 18 Feb 16h00 CET, Free

In this webinar, Whiney will discuss MGARD, a multigrid-based lossy compression tool for scientific data with rigorous error bounds.

Research Software Engineer Early Career Panel Event - US-RSE and Academic Data Science Alliance - 23 Feb, 2pm ET, Free

Of possible interest for trainees your team works with:

Given the interdisciplinarity and relative adolescence of the fields of Data Science and Research Software Engineering, it is unsurprising that career paths in the field are confusing and opaque. This career panel will offer attendees the opportunity to hear from data scientists and research software engineers about their career paths, the skills expected of these positions, where and how to seek these types of positions, and what to expect when working in these fields.

SIAM Conference On Computational Science and Engineering - 1-5 Mar, 8am-7pm CST, $165-365, $50-$90 for students

SIAM CSE21’s extensive program has too many sessions to sum up here, but if you’re interested in applied math and research computing, you’ll likely find something here.

For better or worse, with the addition of user-defined functions, Excel is now inarguably a full-fledged programming language.

Papers With Code, the project that’s highlighting ML preprints that include code and bundling them together, is now indexing data sets.

Apache Arrow, a format/library for columnar data representation with minimal serialization/deserialization overhead for handing off between different kinds of services, is in version 3.0.

On-the-fly x86 emulation in the browser, using WASM.

Matrix Multiplation in WebGPU with Safari.

We’ve had incident reports here for software and systems - here’s a burgeoning list of AI Incident Reports for incidents in deployments of AI/ML systems.

In defence of nano.

A use case for property-based testing? If you use JSON anywhere, push some big numbers through your system and see what happens.

While we’re all waiting for GitHub codespaces to go into GA, github1s may be the next best thing.

Data visualization of 67 years of Lego sets.

Data visualization of 30 months of electricity usage in Manchester, 1951-1954, using cut out cardstock.

A visual guide to ssh tunnels. Put here not only as a technical reference but as a nice example of what can be done visually with small consistent repeated use of iconography.